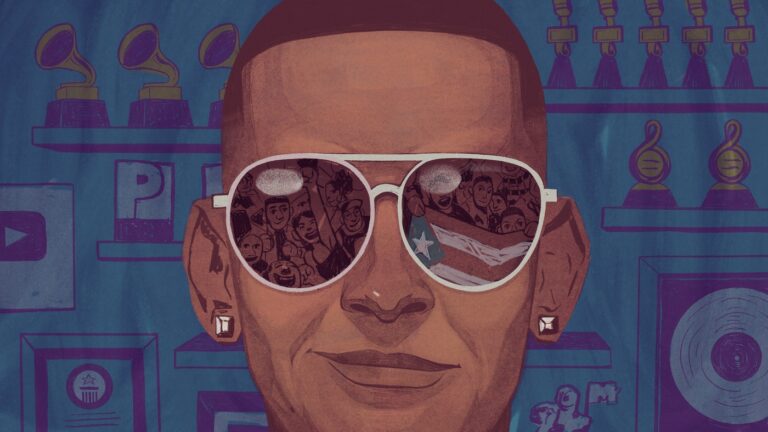

Daddy Yankee helped build a global market for reggaeton — but he also illustrated how much political power the genre wields.

Victor Bizar Gomez for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Victor Bizar Gomez for NPR

Daddy Yankee helped build a global market for reggaeton — but he also illustrated how much political power the genre wields.

Victor Bizar Gomez for NPR

By the time Daddy Yankee plays “Gasolina” one August night at Atlanta’s State Farm Arena, the crowd rumbles so loud it feels like the venue will cave in on itself.

It’s a show that’s been months in the making: La Última Vuelta, Yankee’s last tour before he retires. He announced the decision to bow out in March, with the release of his first studio album in a decade. LEGENDADDY, as he so aptly named it, found the reggaeton veteran giving himself his flowers for a career that’s spanned more than three decades and made him a household name across the world.

“Gasolina” is Yankee’s encore, and the boisterous crowd has been anxiously awaiting the familiar, roaring motors all night. Yankee wants the payoff — the screams, the singing along, the perreo — before he walks off this stage one last time. And his fans, ranging from teenagers to boomers and repping flags from almost every single Latin American country, gladly deliver.

“Gasolina” is undoubtedly one of the most significant songs not just in Yankee’s career, but Latin music as a whole. It was released as the lead single for Barrio Fino, the 2004 album that debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Top Latin Albums chart — the first reggaeton album to do so — and went on to become the best-selling Latin album of the decade. The first reggaeton song to be nominated for the Latin Grammy for record of the year in 2005, “Gasolina” elevated the already popular reggaeton formula of breakneck verses, a booming beat and a woman’s sensual hook (from the undersung vocalist Glory) to a global platform. O sea, un temazo — it’s catchy as hell.

And on this particular night, it feels like the Puerto Rican maestro is winking at the double-meaning of the bridge in this context.

Tenemos tu y yo algo pendiente

Tu me debes algo y lo sabes.

(We have something pending, you and I

You owe me something and you know it.)

Hearing “Gasolina” live now is bittersweet. It’s a song that revolutionized the music industry, because that’s what Yankee was always aiming for. In the years since its release, reggaeton has become a global powerhouse, blasting from fitness studios and chain restaurants across the U.S. And whether or not Yankee’s retirement means he’ll never perform or make music again, the trailblazer’s highly publicized farewell signals the genre has entered a new era. In a moment where reggaeton — a movement started in underground bars and homemade studios — has reached its commercial apex, how will artists propel the genre forward?

YouTube

Born Ramón Luis Ayala Rodríguez in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Daddy Yankee grew up in public housing and originally dreamed of becoming a baseball player. One night while taking a break outside a studio, gunshots rang out and a stray bullet from an AK-47 struck his leg. He spent more than a year in recovery, and even though it shattered his athletic aspirations, he realized music could be his way forward.

Yankee belonged to a class of pioneers that included Don Omar, Ivy Queen, Wisin & Yandel and producers like DJ Negro and DJ Playero. Throughout Puerto Rico, they were building off the reggaeton groundwork laid by Panamanian artists like El General, who’d helped combine reggae, dancehall and Spanish-language hip-hop — genres that were mixing due to Jamaican migration to Panama, Panamanian migration to New York — to create a new sound.

But as exciting as that explosion of creativity and melange of Caribbean genres was, reggaeton lacked financial support both in PR and abroad, says Leila Cobo, VP of Latin for Billboard and author of Decoding “Despacito”: An Oral History of Latin Music.

“Daddy Yankee had to create his tapes in his little home studio, sell them from his car, and there was no one he could call and say, ‘Do this for me,’ ” she says. “There was no capital. He had to do everything on his own. It was very, very hard. There was nothing, there was no infrastructure. So [he and other artists] really built it from the ground up.”

While artists like Tego Calderón focused on socially-conscious lyricism, Yankee honed in on the business opportunity. Katelina Eccleston, the music historian of the platform Reggaeton con la Gata, says that Barrio Fino pushed for space on Spanish-language broadcasting, especially in the U.S., and proved that reggaeton could successfully get radio play around the world.

A lot of Spanish-language broadcasting at the time focused on pop and rock en español, as well as regional music. Latin artists like Shakira rebranded, crossing over to be played on English-language stations. The Latin music industry in and outside of Latin America looked down on reggaeton as vulgar, overtly sexual, poor or working-class music.

But Daddy Yankee’s breakthrough started to reverse that trend. “Daddy Yankee is the perfect product,” Eccleston explains. “He set the precedent and really raised the bar for how reggaeton artists should be approached, how they should be invested in and how the genre should be respected.”

And Barrio Fino‘s success only marked the beginning. Yankee consistently churned out banger after banger in the form of albums like El Cartel: The Big Boss, Talento de Barrio, and the more pop-oriented Prestige in the following years. He collaborated with stars in the American market, like Snoop Dogg and the Afro-Puerto Rican, reggaeton-dabbling N.O.R.E. and intelligently positioned himself, Eccleston says, as the Latin idol amongst their ranks.

But it’s not just the creation of an image or social clout that led to his colloquial nickname, “The Big Boss.” Cobo links a big part of Yankee’s commercial success to the fact that he stayed independent through El Cartel Records, the label he founded in 1997. He retained ownership of his masters — a power move he has said started off more or less unintentionally, because he just couldn’t get signed without being cut a short deal — and partnered with major labels like Sony, Universal and Interscope for distribution over the years.

“He really showed several generations of artists that this was economically viable,” says Cobo.

In 2017, more than a decade after “Gasolina” first hit airwaves, the genre reached another turning point. Puerto Rican singer Luis Fonsi was working on a track that would go on to change the course of Latin music history: “Despacito.”

“Luis Fonsi finished the track without reggaeton in it, and then after he took it to his producers, they said, ‘You know what?’ Between all of them, they said, ‘It feels it needs something different. It needs something urban,’ ” says Cobo, who detailed the song’s creation and impact in her book. “And ironically, they didn’t go to Yankee first.”

Nicky Jam took the first pick, until other commitments caused him to step back from the project. Then, Yankee became the obvious choice — and the song took off. A Justin Bieber feature on the remix only solidified its status, and the remix tied, at the time, with Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men’s “One Sweet Day,” for most time spent at the No. 1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart (16 weeks), topped the Billboard Hot Latin charts for 42 weeks (another record) and became almost inescapable in public. In 2020, “Despacito” became the most-watched video at that point in YouTube’s history with over 7 billion streams.

The song ushered in an era of Latin music that even saw Beyoncé jumping on a J Balvin and Willy William remix. But it also solidified Daddy Yankee’s place in pop, and signaled a move toward a bit of a cleaner, more palatable image and sound for reggaeton. All of a sudden, the English-language industry realized it could get in on a profitable market — all artists had to do was get a verse on a reggaeton song already tearing through the club scene.

“The thing about reggaeton is that just off of its pure existence — Panama, Puerto Rico, New York, Jamaica — it’s an international genre, period. It has many homes,” says Eccleston. “So it was bound to be successful in many parts of the globe. I think what Daddy Yankee did differently is that he scaled it exponentially.”

And he made room for younger generations along the way. Cobo credits Yankee’s power with lending a model for youth in Puerto Rico that has partially resulted in the island’s ever-growing pool of talented singers, writers, producers and engineers. But his reach is felt outside of his home, too.

Becky G says she grew up listening to Daddy Yankee — her young “cool” parents played his music in the house. She first collaborated with Yankee when he was one of the writers and producers on her song with Natti Natasha, “Sin Pijama,” in 2018. She describes his presence as godfather-like. “If it weren’t for Yankee vouching for us,” she says, “A lot of people tried to discredit what we were doing as women.”

She remembers the success of her 2017 single “Mayores” and Natti Natasha’s “Criminal” being attributed to the presence of their male collaborators — Bad Bunny and Ozuna, respectively. But she says Yankee respected and believed in her and Natti Natasha’s craft, and later gave them room to rep women empowerment on the “Dura” remix in 2018. Fast forward four years, collabs between exclusively women artists in reggaeton aren’t only more common, but they sell. Earlier this year, Becky G’s “MAMIII” with Karol G — a big middle finger to a toxic ex — debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Latin Songs chart.

“I feel a responsibility now moving forward to just be true to what [Yankee] saw in us — being empowered, young Latinas who want to have a seat at the table, who want to be in the driver’s seat,” says Becky G. “He’s always been so encouraging of that. It’s funny, you know, how he sometimes references himself as ‘the big boss’? We walk in, me and Natti, and we’re like, ‘the little boss!'”

They’re two of the younger superstars featured on LEGENDADDY — along with Bad Bunny, Myke Towers, Sech, Rauw Alejandro and dembow prophet El Alfa. A businessman until the very end, the album was a strategic move on Yankee’s part. He’s “handing down” to the artists he made space for, all already so successful in their own right — a level of stardom Yankee has, in many ways, helped secure for them.

YouTube

Daddy Yankee pushed forward, eventually creating his own business model around reggaeton because he didn’t really have another option. Today, it’s a completely different industry. Bad Bunny is the most streamed artist in the world and Un Verano Sin Ti just became the first Spanish-language album to receive an album of the year nomination from the Grammys.

There’s momentum, money and a built-in global audience for the genre. But if reggaeton came up through the freedom and resistance of underground perreo, will the new stakeholders carry on that drive set by Yankee’s generation to create something fresh and disruptive to the industry?

Sech says that expansion is already underway. “We have mambo from Rosalía, we have pop from Rauw, we have Quevedo doing house,” he says. “It’s all happening in Spanish, and it’s helping our genre grow.”

Musically, the landscape is only getting richer. There’s Shakira and Ozuna doing a bachata pop, Rauw wading deeper into dancefloor futurism (produced by DJ Playero, no less) and Tokischa crooning explicitly across dembow, corrido and EDM tracks.

That last example is important, because it’s part of what Eccleston says is a larger expectation, in today’s industry, for artists to take on the personal and the political in their music, and prioritize inclusivity. For Tokischa, whether intentional or not, the sexual openness of her music does that work.

“There is a collective, racist understanding that reggaeton can be great, but also we can’t play the vulgar stuff in front of mami y papi,” says Eccleston. “But it’s not for mami y papi, you know? It was created by sexually liberated adults for other sexually liberated adults.”

And it’s not just Tokischa. Bad Bunny continues to authentically wrap political statements about Puerto Rico’s colonial state into his music, all while disrupting gender norms and uplifting queer and women artists at his shows. This past summer, that meant inviting artists Villano Antillano and Young Miko, who are at the core of the trans and queer Latin trap movement, onstage in San Juan.

But despite strides in reggaeton’s commercial popularity, Afro-Latino artists beyond Sech and Ozuna still rarely take center stage in the movement. Reggaeton is a genre that still struggles to constructively talk about race, despite being built and actively profiting off Black culture and sounds in the Caribbean and abroad. At this year’s Latin Grammys, Rosalía accepted the album of the year award while her bachata song, “La Fama,” blasted in the background — but Black Latinx artists who’ve created those sounds don’t get the same reception or recognition.

“There’s this desire to try to clean reggaeton,” says Eccleston. “This whitening or blanqueamiento of reggaeton is definitely pervasive in the space.”

Aside from the genre’s issues with inclusivity, family-friendly reggaeton pop songs will continue to permeate the airwaves and Billboard charts; that’s part of Daddy Yankee’s legacy, after all. He cracked the code, and helped build that market from scratch. But he also illustrated how much political power reggaeton wields.

Yankee set a precedent of social and artistic resistance by taking a genre from working-class neighborhoods in the Caribbean and popularizing it into one of the most recognizable and profitable sounds in today’s landscape, even though the Latin music industry initially looked down on what he was doing. Now, as he bids his farewell, reggaeton has reached a point where that defiance set by Yankee’s generation can take new shapes of rebellion and experimentation, both in sound and in politics — even if perreo is no longer confined to underground clubs and garage parties, but now fills entire stadium and arena tours.

“Reggaeton is music with so much happiness, so much movement, so much expression,” says Sech. “And everyone has their own definition of art. But if reggaeton doesn’t have that sense of street [to it], it’s not what we started with.”