If all you knew about León Salvatierra were his résumé, you could be forgiven for assuming he’s living the dream life. He has a doctorate in Hispanic languages and literatures from UC Berkeley and a master of fine arts in poetry from UC Davis, where he is a professor in the department of Chicana/Chicano studies. Combined with Salvatierra’s easy manner, ever-present grin and dry sense of humor, these accomplishments complete the image of an artist blessed with good fortune, comfortable in the life of letters in a country that doesn’t always reward poets.

But this veneer falls away when you learn Salvatierra’s biography and delve into his poetry. His father died in his 40s of alcoholism; at 15, he migrated from Nicaragua to escape the fate of becoming a child soldier for the Sandinista regime. Arriving in the U.S. with no documents, very little English and undiagnosed dyslexia, Salvatierra had little reason to imagine himself inside the life of the mind.

The opening lines of his poem “At the Cemetery” bring those years to life:

“In Nicaragua shrubs grow in the winter / with the breath of rattlesnakes / Two decades of war, alcohol, and other grievances / had overcrowded the neighborhood of the dead / I walked with my hands on my head / back and forth trying to remember / where my father’s grave was.”

Benedictions for the dead recur in Salvatierra’s poetry, but so do sly critiques of consumerism, details accumulating in service of not only sorrow but laughter and the shock of juxtaposition.

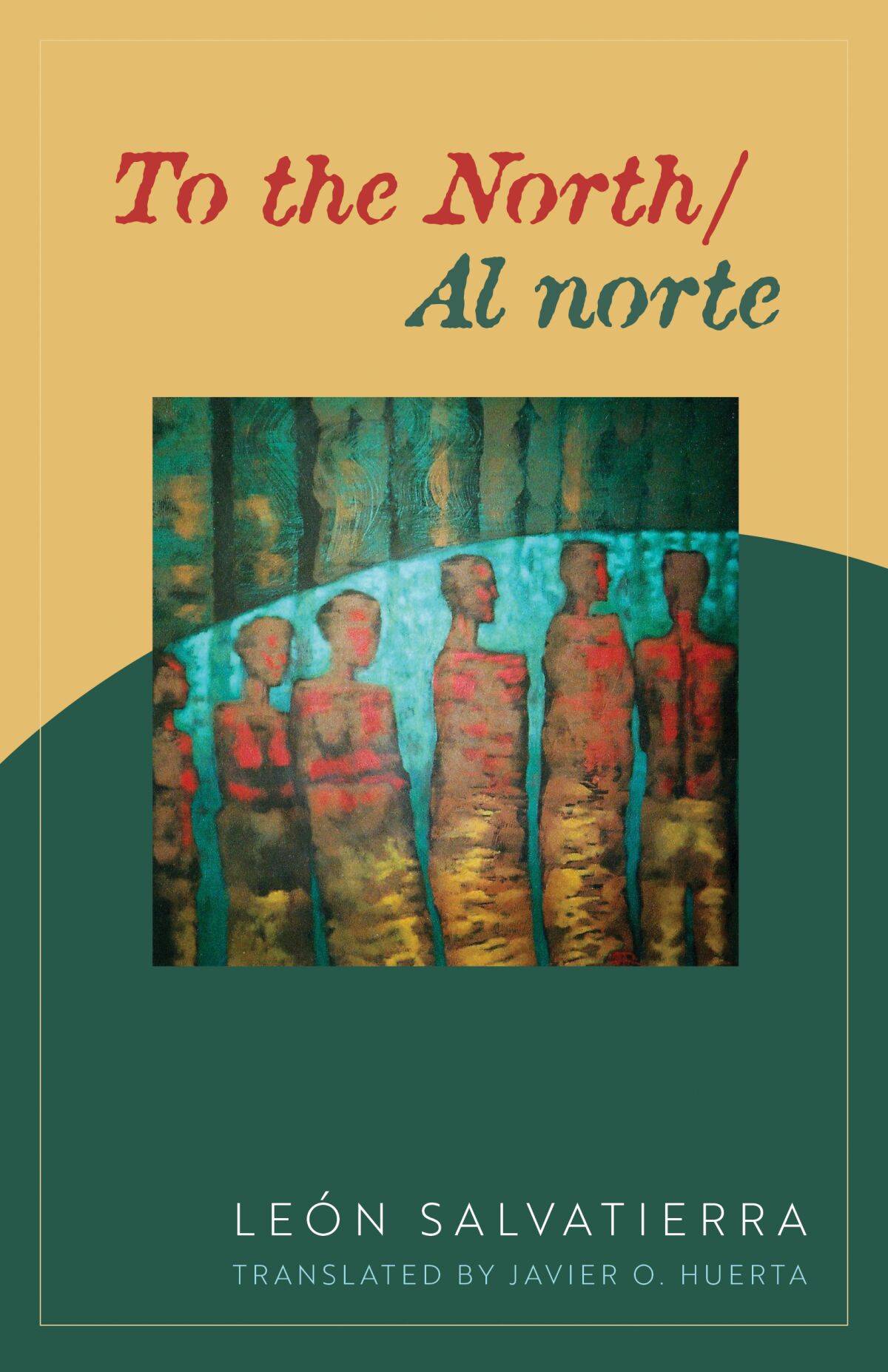

This week, the University of Nevada Press brings out a bilingual edition of Salvatierra’s first poetry collection, “To the North / Al norte.” Largely translated by Javier O. Huerta, it is simultaneously heartbreaking and hilarious — even more so if you can read it in both languages.

Poised to break through into the American consciousness, Salvatierra spoke to The Times about the genesis of this collection, the art of translation and the writing life of an immigrant. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

(University of Nevada Press)

This book first appeared in a Spanish edition in Nicaragua. The new edition was translated by Huerta even though you are yourself a translator. How exactly did it come together?

Javier and I met as graduate students at UC Berkeley in 2007 in a poetry workshop led by the late Chicano poet Alfred Arteaga. I only wrote poetry in Spanish then. After class, Javier and I often went to a nearby bar where we continued our conversations. That’s how we became great friends; later we were roommates for 10 years. When “Al norte” was first published in 2012 in Spanish, Javier was teaching a course on the literature of the undocumented at Berkeley. He wanted to teach the title poem of my book, but he had to translate it into English. Then he decided to translate the entire collection. He sent me a Word document with the translation completed. We put aside the manuscript for many years.

My involvement with the translation took place relatively recently when I decided to start writing poetry in English. While working on my poems for my MFA thesis, I was also reviewing Javier’s translation. I made changes to the Spanish versions and, consequently, I had to revise the English versions as well, but they were minor edits. The most significant change in the new edition is the replacement of three poems with three new poems, which I wrote in Spanish. I translated [these] three new poems myself. The new pieces capture my experience living in the U.S. for the last decade, such as being a father and witnessing the housing crisis here.

Every time we begin, we face the negation of language, a blank page that somehow mirrors the void inside us.

— León Salvatierra

In a note to the reader, you observe: “My sense of being an impostor intensified when I entered illegally into the United States. I felt like an intruder.” Could you talk about this struggle with identity and belonging, and how you approach it through poetry?

The struggle is inherently part of the immigrant experience anywhere in the world. It’s even more challenging for immigrants with no “legal” documents affirming and reaffirming their social identities. In our society, soon after we are born, we are bombarded with official documents: First, we get a birth certificate, then a Social Security card, a driver’s license, school diplomas, insurance documents, all the way to our death certificate, which of course we never get to read. In my experience, the absence of official documents generated a sense of falseness, a lack of authenticity and a kind of voided identity.

Last night, I read a wonderful poem by Lorna Dee Cervantes, “The Refugee Ship,” where she uses the metaphor of a ship that never docks to talk about her struggle with identity and belonging. Her poem underscores the feeling of being an orphan to a language. I enjoyed her forceful irony: a poet who speaks of having a lack of language. People often think of poets as special people with an excess of language. I think it’s quite the opposite. Every time we begin, we face the negation of language, a blank page that somehow mirrors the void inside us.

Santa Claus is mentioned in several of your poems, including in “Santa’s Diet,” which you dedicate to your son. Why Santa Claus?

Growing up in Nicaragua, we didn’t have Santa Claus as a Christmas reference. Instead, we had El niño Dios (the baby Jesus), who supposedly would bring us gifts so long as we behaved. The first Christmas I spent in the U.S. in 1988, the image of Santa was everywhere. The baby Jesus was overshadowed by the extravagant Santa. This image was constantly associated with exhilarating consumption, not with the religious rituals I had experienced as a kid. That’s how I view Santa, as a cultural signifier of consumption.

In the title poem, the narrator recounts a harrowing crossing into the United States. The poem is, in some ways, a homage or benediction for those who did not survive the crossing. Was that your intent?

Initially, I just wanted to write a good poem about crossing the border between Guatemala and Mexico. In the revision process, I realized it was partly a homage to those who die on their journey. After I finished revising, I knew that not only did I have a new poem in my hands, but I also had a book of poems to write. Don Eduardo is the name given to a character who dies after crossing the Suchiate River at the border. The narrator is unsure if Don Eduardo is really his name, but that’s what he will call him. Understanding [this] character made me reflect on my border-crossing experience as a collective struggle. The name reappears in other poems in the collection. On the dedication page, after my family, you find the book is also dedicated to Don Eduardo. But he is not a specific person. Much like in Corky Gonzales’ poem “Yo soy Joaquin,” where Joaquin is a symbol for the Chicanx experience, Don Eduardo is a symbol for the experience of the Central American diaspora.

In the collection’s introduction, the poet Francisco Aragón calls you “a welcome addition to a chorus of poets from the Central American diaspora.” How do you view your role within this chorus?

I’m honored to be welcomed in this community of writers. My role is to write poetry to the best of my ability. The total commitment to their craft may be the only responsibility writers should have. I don’t think my nationality and experiences are the defining features of my poetry. What distinguishes a poet’s voice is the form in which they process their lived experiences, visions, dreams and memories: their rhythms, cadences, the way they cut their lines, how their words move on the page, the imagery of thought, the pulse of their allusions and associations, the way they make the common seem uncommon, the familiar unfamiliar, the real unreal and vice versa. The form is how we imagine, breathe, walk and sing as poets. As William Yeats would have defined it, the form is what distinguishes the dancer from the dance.

Olivas is an attorney, playwright and author of 10 books, including “How to Date a Flying Mexican.”