It was a crisp fall day when I asked our daughter Penny about the new book she was reading. “How are you liking Ramona?”

She was holding my hand as we walked, but suddenly she stopped. “Mom,” she said, looking up at me, smiling wide. “I want to be Ramona.”

We walked again, hands swinging slightly. I loved that she had connected with Ramona Quimby, this little girl who puzzled through her childhood with equal parts disappointment and delight. But I also felt a twinge of concern. Penny was 8 years old at the time, and we hadn’t yet encountered anyone with physical or intellectual disabilities in the pages of a book. Where would she find a little girl with hopes and dreams and potential and challenges, who also had Down syndrome?

In recent years, the representation of kids with disabilities in middle-grade and YA fiction has increased exponentially. In 1990, when the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) was passed in Congress, more and more students with disabilities were integrated into typical classrooms. According to a study of Newbery winners from 1975 to 2009, this year also saw a shift in the representation of kids with disabilities within children’s literature. Children with deafness, ADHD, stutters, and other learning disabilities have all appeared in chapter books published in the subsequent decades. Their presence reflects a newfound assumption that children with disabilities belong in our classrooms, and therefore they belong in our stories. Still, in the beginning, that presence within the stories seemed a bit precarious. As the authors of this study noted, many of these books “eliminated the character with the disability at some point.” Characters with disabilities often died, or their disabilities were miraculously cured. Their disability served as a plot device or a means by which other characters learned and grew.

Read More: Inside the Massive Effort to Change the Way Kids Are Taught to Read

As Penny got older, we looked for books that offered a fully realized portrait of kids with disabilities. We have read and appreciated novels like Fish in a Tree (dyslexia), Out of My Mind (cerebral palsy), and Wonder (facial deformity). None of the kids in these books die, and none of their disabilities are miraculously cured. Wonder, in which R.J. Palacio depicts Auggie Pullman, who has a physical disability and also a complex and endearing emotional, intellectual, and family life, became a blockbuster bestseller. After we read it, I asked Penny if she saw herself in any of the characters. She was 10 at the time, and she said, “Yeah. Auggie. Because, you know. I was born with something too.” After we read it, I asked Penny if she saw herself in any of the characters. She was 10 at the time, and she said, “Yeah. Auggie. Because, you know. I was born with something too.”

As children with disabilities have integrated more fully into classrooms and other public spaces, so too they have received fuller representation within the pages of books. And yet, in all these stories, the kids have tremendous intellectual ability, even when their disability prevents adults and other children from being aware of it. It is as if their physical disability or neurodivergence is mediated by the presence of intellectual acuity.

But what about the kids whose intellect is not their superpower? Even in a world that is becoming more inclusive, we struggle to receive people with intellectual disabilities as fully human. The r-word is still used as a slur. Bumper stickers make fun of riding the “short bus.” And our children’s literature still seems to prefer stories about people with brilliant minds “trapped” inside bodies that an able-bodied world sees as broken or impaired to stories of kids who learn slowly.

When I realized we still hadn’t read any books with characters with Down syndrome, I started asking around. I learned about the Dolly Gray Award as well as the Schneider Family Book Award. Both recognize authors or illustrators of children’s books that embody the experience of disability. One of the Dolly Gray award-winning books, A Small White Scar, from 2008, includes a brother with Down syndrome, but he is a secondary character in a story set in the 1940s, so it wasn’t a great fit for Penny. I corresponded with Emily Briano, a high school librarian and mother of a 14-month-old with Down syndrome. Despite searching her library catalogs, Amazon, her ebooks, her audiobook subscription services, and Goodreads, she had not encountered any chapter books with main characters with the condition.

Read More: Artist Oliver Jeffers Wants to Paint the World Out of a Corner

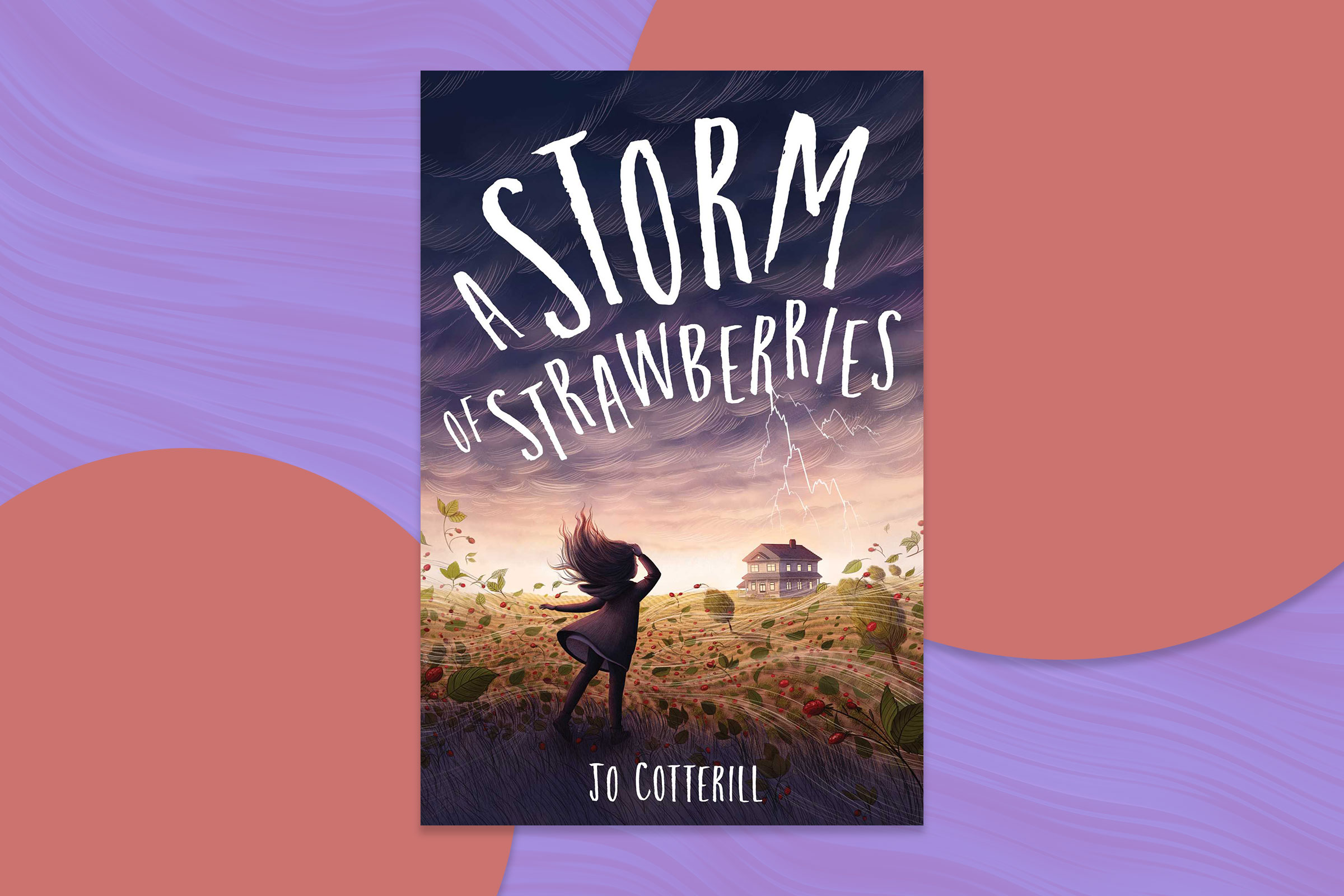

The one book I’ve found so far that offers a character with Down syndrome at its center is Jo Cotterill’s A Storm of Strawberries. Here 12-year-old Darby is both charming and annoying, petulant and compassionate. She enjoys putting on makeup and listening to music. She doesn’t understand many unspoken social cues. Penny is now 16, and we recently started reading this one together. She nudged my side when we learned that Darby does “this thing where I talk to myself.” We giggled when Darby mentions that “dancing is the only exercise I like.” These little moments connected to our lived experience, as did Darby’s love for her family and the way her thoughts are both very straightforward and sometimes hard to express. Darby shares memories of her childhood throughout the book, and those memories got us talking about Penny doing some writing of her own, using photographs from the past as a prompt.

A Storm of Strawberries by Jo Cotterill

Heather Avis, founder of the Down syndrome advocacy organization the Lucky Few and mother of three kids, two of whom have Down syndrome, has written two picture books with characters with disabilities. “It is a challenge to write about a person with an intellectual disability,” she told me. “And it is a challenge for people with intellectual disabilities to write about themselves and express themselves.” Perhaps authors worry that they cannot justly and accurately portray the inner world of a person with intellectual disabilities. Perhaps we need to convince the publishing industry that characters with intellectual disabilities have stories worth telling too.

Just as we have seen the benefits of greater racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual identity representation in children’s literature, we need an array of characters with both physical and intellectual disabilities within our books. We need more books like this for kids like Penny, so that they can find their own experiences mirrored back to them and know that they are not alone. But we also need these books as portals for kids who have never had a friend, sibling, or neighbor with Down syndrome, for typically developing kids who don’t know that there are ways to communicate with kids who are nonverbal, for kids who might be able to find a point of unexpected connection with someone who at first seems radically different.

Our public spaces are becoming more inclusive of more people, and our children’s literature needs to reflect these shifts. Our stories tell us who matters enough to write about. Our stories shape our imaginations. Our stories tell us who belongs.

More Must-Read Stories From TIME