Mali said on Monday that it had killed a high-value Islamist commander who helped lead a 2017 attack in which four American and four Nigerien soldiers were killed alongside an interpreter.

The U.S. State Department had put a $5 million bounty on the head of the commander, Abu Huzeifa — a member of an affiliate of the Islamic State — after his participation in an attack in Tongo Tongo, Niger, on American Green Berets and their Nigerien comrades.

At that time, the attack was the largest loss of American troops during combat in Africa since the “Black Hawk Down” debacle in Somalia in 1993.

In a post on social media on Monday, Mali’s armed forces said that on Sunday they had “neutralized a major terrorist leader of foreign nationality during a large-scale operation in Liptako” — a tri-border region that contains parts of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger.

The three countries, all led by military juntas, have teamed up to fight extremist violence under a new partnership, the Alliance of Sahel States — something critics have said is an attempt to legitimize their grip on power.

Officials at the U.S. State and Defense Departments said on Tuesday that they were aware of the report of Abu Huzeifa’s death, but were seeking more information.

The U.S. declared eight men wanted for the Tongo Tongo attack. With Abu Huzeifa’s death, only one — Ibrahim Ousmane, better known as Doundoun Cheffou — is thought to be still alive. In 2021, France announced that it had killed the principal planner of the attack, the head of the Islamic State affiliate, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui.

The affiliate, now called the Islamic State Sahel Province, has declared allegiance to the Islamic State. The core leadership was decimated after Al-Sahraoui was killed but they have regrouped and are “in the process of establishing a pseudo-state” in the border areas between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, according to ACLED, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

Broadcasting the report of Abu Huzeifa’s death on Mali’s state television channel, an announcer described him only as a “foreigner.” Analysts said his origins were in the disputed territory of Western Sahara, controlled by Morocco, or in the Algerian camps where refugees from the territory have spent the past 40 years.

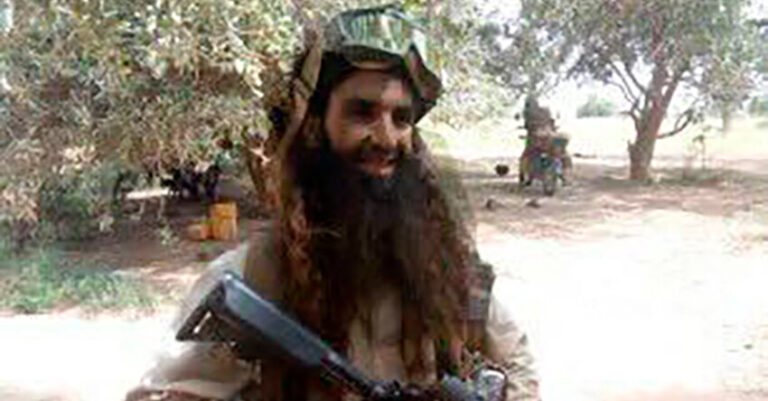

In photographs and video broadcast by the channel, Abu Huzeifa was shown with a flowing beard and mane of hair, a slight man in fatigues and goggles, holding an ISIS flag and a gun.

“The Malian army succeeded where the armies said to be the most powerful in the world failed,” said Abdoulaye Sacko, the announcer.

Mali has been in crisis since 2012, when rebels and jihadists took control of swaths of its desert north. The intervention of foreign forces — led by France, which deployed thousands of troops — failed to stop the unrest.

In 2020, coup plotters overthrew Mali’s elected government, using the security crisis to justify their power grab. But since then the ruling junta has pursued the same military-first strategy that the foreign forces did, and nearly four years later, analysts say the situation is worse.

After a ten-year fight against the Islamists, French troops pulled out in 2022. The junta in Mali turned instead to Russian military advisers and mercenaries with the Wagner group, who were accused of committing atrocities in the course of pursuing the militants.

“The military approach by itself can’t bring lasting solutions,” said El Hadj Djitteye, director of the Timbuktu Center for Strategic Studies on the Sahel, a think-tank based in Bamako.

What could make a difference, he said, is helping to find people alternative ways of making a living “to respond to the needs of the population and reduce recruitment of young people into the terrorist groups.”

Despite delaying elections, Mali’s junta has appeared to enjoy enduring public approval, particularly in Bamako, the Malian capital. Last November, it boosted its popularity by recapturing the northern city of Kidal, which had been in the hands of separatist rebels for a decade. When they heard that Kidal had fallen, dozens of people waved flags at Bamako’s Independence Square in celebration.

Residents of Bamako, welcomed the news of Abu Huzeifa’s death on Tuesday. But he has less name recognition than other jihadists fighting in Mali, and most citizens were too preoccupied with the difficulties of daily life to do much celebrating.

Debilitating electricity cuts — many areas get less than six hours of power per day — have forced many businesses to grind to a halt, with dire consequences for the economy. A severe heat wave, caused in part by climate change, has precipitated a surge in deaths and hospital admissions in Bamako.

On Tuesday, Bamako residents joked that the Malian junta should collect the $5 million bounty from the Americans — and use it to try to stop the outages.

Eric Schmitt contributed reporting from Washington.