Hundreds of Kenyan police officers have been training since late last year to embark on the deployment of a lifetime: helping lead a multinational force tasked with quelling gang-fueled lawlessness in Haiti.

The deployment has divided the East African nation from the onset. It touched off fierce debate in parliament and among officials in at least two ministries about whether Kenya should lead such a mission.

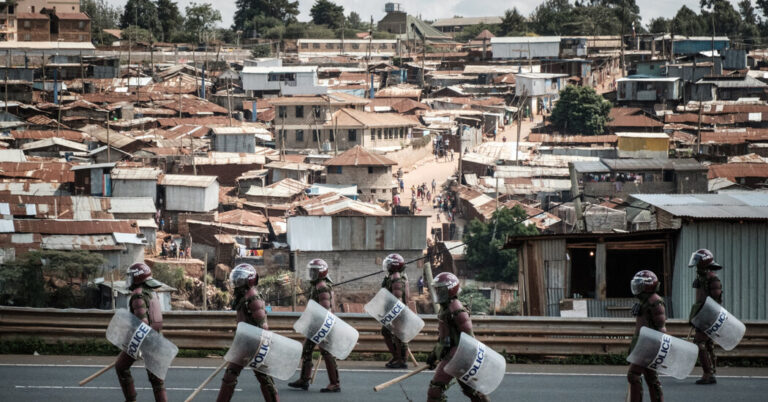

The courts also sought to block the deployment, while activists and human rights groups, citing a history of abuse and unlawful killings by the Kenyan police, roundly denounced it.

But the plan received unwavering support from its main champion, President William Ruto of Kenya, who said responding to the worsening crisis on the Caribbean nation was a call to “serve humanity.”

Now, months after finishing their training, Kenyan officers were called back from leave this week in preparation for leaving for Haiti, according to interviews with several police officers who are part of the planned deployment. The officers said they have not been given a precise date but anticipated that they would arrive in Haiti this month.

Their expected departure comes as the United States, which is largely financing the plan, steps up efforts on the ground in preparation for the arrival of the multinational force in Haiti, including building a base of operations at the country’s main airport.

The looming deployment comes as Mr. Ruto prepares for an official state visit with President Biden on May 23, which will provide a brief distraction from a slew of domestic challenges, including deadly floods, mounting debt and a major scandal over fertilizer subsidies.

The international mission is expected to consist of 2,500 members, led by 1,000 Kenyan police officers. The rest of the deployment will come from more than half a dozen nations that have pledged to provide additional personnel.

With Kenyan police officers expected to be the first to arrive in Haiti, some security experts have questioned their readiness to support Haiti’s beleaguered police and face off with the well-armed and highly organized Haitian gangs that have taken control of much of Port-au-Prince, the capital.

“This is new territory for the Kenyan forces,” said Murithi Mutiga, the Africa program director for the International Crisis Group.

Even though the security officers chosen for the mission are some of Kenya’s best trained, he said that “they will essentially be venturing into an unknown path where the risks remain considerable.”

Haitian gang leaders have vowed to fight the deployment, raising concerns of even worse violence in a country where thousands of people have been killed in recent months and more than 350,000 have fled their homes in the past year.

The United Nations-backed mission has lingered in limbo since March, when Kenya said it would pause the effort after Prime Minister Ariel Henry of Haiti resigned. Gangs had taken over the Port-au-Prince airport, preventing Mr. Henry from returning home from an overseas trip.

After a new governing council was formed in Haiti in April, Mr. Ruto said he was ready to move ahead with the plan.

Mr. Ruto’s critics have accused him of illegally pursuing the deployment and not publishing a document stipulating how Kenyan forces can operate in Haiti. They also plan to file another legal challenge accusing his administration of contravening earlier court orders around the mission.

Kenyan government officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Millie Odhiambo, a Kenyan lawmaker who serves on the defense, intelligence and foreign relations committee in parliament, said Mr. Ruto should deploy officers at home to crack down on criminals and terrorists wreaking havoc in some parts of the country.

Given the intense level of violence in Haiti, she also questioned the government’s decision to send the police rather than the military.

“This mission is a death trap,” she said.

The mission’s legal and political roadblocks have frustrated Kenyan police officers who have been waiting for months to go to Haiti.

Officers interviewed for this article, who asked not to be identified because they were not authorized to speak publicly to reporters, said hundreds of officers turned out for the selection process last October.

Some 400 officers were chosen for the first deployment and began training, with an additional 100-member support staff that includes medics. Another, similarly sized group would also prepare to deploy soon, they said.

The officers were chosen from Kenya’s General Service Unit and the Administration Police, two paramilitary units tasked with dealing with everything from riots and cattle rustling to protecting borders and the president.

The officers said they received physical and weapons training from Kenyan and American security personnel and were given details about how Haitian gangs operate.

They also took French classes and lessons on human rights and Haiti’s history. The police officers said they were aware of previous failed international interventions in Haiti. But they argued that those interventions had been largely viewed by Haitians as occupation forces, while their goal is to support the local police and protect civilians.

Besides the prestige that comes with serving abroad, officers said the additional pay that comes with their service is another motivation.

The normal salary for these Kenyan officers is $350 a month, which a national task force last year recommended be raised by 40 percent. In the meantime, with families to support and loans to repay, officers said they were in debt and unable to make ends meet.

Some officers said it was not clear how much more they would be paid once they are in Haiti and, if the worst happens and they were to be killed, what compensation their families would receive.

For now, regional experts say President Ruto of Kenya faces the daunting challenge of forging ahead with an intervention fraught with risks. Mr. Mutiga of the Crisis Group said the government has not done enough to explain the mission’s objectives to Kenyans.

“Given that Kenya is a relatively open society, this is a political risk by the Ruto administration,” Mr. Mutiga said. “If you have substantial casualties, it could be politically problematic.”