Some 375 million years ago, armored fishes ruled a watery world. Known as placoderms, these primitive jawed vertebrates came in all shapes and sizes, from small bottom-dwellers to giant filter-feeders. Some, like the wrecking-ball-shaped Dunkleosteus, were among the ocean’s earliest apex predators.

Few of these ancient oddities were weirder than the aptly named Alienacanthus. Discovered in Poland in 1957, this Devonian Period fish was initially known for a set of large, bony spines. But the recent discovery of a fossilized Alienacanthus skull, described in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Royal Society Open Science, reveals that these spines were actually the fish’s elongated lower jaw. Measuring twice as long as the rest of the fish’s skull, this lower jaw gave Alienacanthus nature’s most extreme underbite, and, perhaps, a stiff lower lip.

“It’s still very alien looking so the name is very fitting,” said Melina Jobbins, a paleontologist who studies placoderms at the University of Zurich and is an author on the paper.

Since its discovery in the 1950s, Alienacanthus is known only from a few fossils discovered in the mountains of central Poland and Morocco. During the Late Devonian Period, these areas were submerged coastlines on opposite ends of a vast sea separating northern and southern supercontinents. But many of these fossils are fragmentary and offer little detail on what this strange fish looked like.

Over the past two decades, researchers have uncovered additional well-preserved Alienacanthus fossils in European museum collections. Dr. Jobbins teamed up with researchers from several of these museums to pool together the fossil bits and more accurately describe the ancient fish.

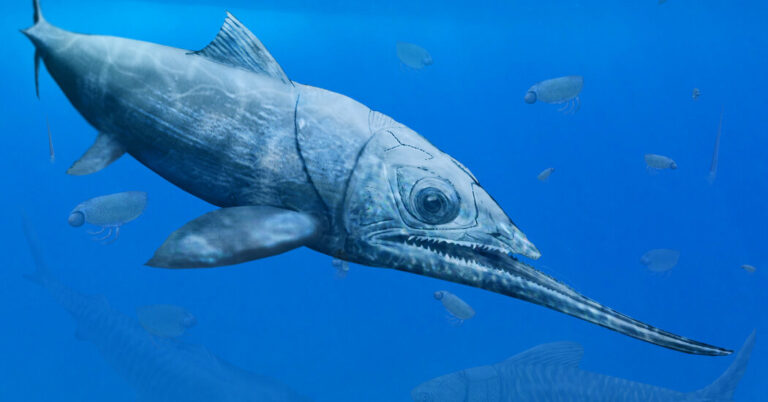

The key to cracking this fishy enigma was a nearly complete Alienacanthus skull measuring more than two and a half feet that originated in Morocco and is currently in the collection of the University of Zurich’s Palaeontological Institute. With the elements of the skull still articulated, the team realized that Alienacanthus’s oddly shaped spines were actually its lower jaw bones. This made the fish even stranger: When it closed its mouth, the placoderm resembled an upside-down billfish with a long, beaklike bottom jaw.

While fishes like swordfish and sawsharks wield dramatic upper-jaw protrusions, very few species possess elongated lower jaw protrusions. Today, this feature is seen only in a group of small fish called halfbeaks. But the relative length of Alienacanthus’s lower jaw was 20 percent greater than a halfbeak’s. Alienacanthus’s jaw was also proportionally longer than similar structures seen in prehistoric sharks and porpoises, making the fossil fish the undisputed champion of the underbite.

The extended jaw may have helped Alienacanthus sift through sediment, which is how modern halfbeaks utilize their shovel-like jaws. Another hypothesis is that the prehistoric fish wielded its lower jaw to stun or injure prey.

Dr. Jobbins thinks the elongated jaw, which was studded with recurved teeth that extended well past where its top jaw ended, most likely served as a trap. “Basically it could invite prey in and then they can’t get out because there’s only one way to go,” she said. Alienacanthus’s shorter upper jaw could move independently of the lower jaw and snap shut once a fish or squid was in too deep.

This snaggletoothed fish is an intriguing evolutionary oddball. As a placoderm, Alienacanthus belonged to the earliest groups of vertebrates to develop complex jaws. The fish provides a glimpse of just how extreme jaws could be right after the now-widespread feature originated.

Alienacanthus also represents one of the final chapters of placoderm evolutionary ingenuity. Within 15 million years of the appearance of Alienacanthus’s toothy mug, these armored fish were wiped out and replaced by sharks.