This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

When he was growing up in Detroit, Walter King wondered why his family didn’t celebrate cultural holidays the way his Jewish and Polish classmates did. So he went to his mother.

“Who is the African God? That’s what I want to know,” he asked her when he was 15.

His mother didn’t have the answer. “Blacks didn’t really have any knowledge of their history and culture before slavery,” she explained, as recounted in the book “Yoruba Traditions and African American Religious Nationalism” (2012), by the scholar Tracey E. Hucks.

The exchange was pivotal: King began a quest to answer his own question. He read everything he could about Africa, taking an African name for himself that would evolve to Ofuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I.

It was while reading National Geographic magazine that he learned of Yoruba. The Yoruba people are one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa, with roots that can be traced to the ancient city of Ile Ife in Nigeria. The slave trade spread their religion throughout the African diaspora, where it is recognized by a variety of names, including Candomblé in Brazil, Santería in Cuba and Vodou in Haiti.

But according to “Making the Gods in New York: The Yoruba Religion in the African American community,” by Mary Cuthrell Curry (1997), “the religion ceased to exist” in the United States — if it had ever existed at all. That is, until Adefunmi I created a branch called Orisa-Vodun and the one-of-a-kind village in South Carolina that embodies it, Oyotunji.

“His mission was to bring the African Gods to African Americans,” Hucks, the scholar, said in an interview. She spoke with Adefunmi extensively for her book and lived at Oyotunji, which she called “a core space for African Americans” and “a mecca where one could go to get initiated.”

About 25 people live there today, but the population reached a few hundred at its height in the 1980s. Scholars estimate that thousands of people globally have been initiated into Yoruba priesthoods through connections to the village.

Between 1956 and 1961 in New York, Adefunmi established three temples in Manhattan; a festival on the Hudson River to honor Osun, the Yoruba river goddess that Beyoncé channels in her album “Black is King”; and a parade that included Black nationalists in African garb on horseback. The Ujamaa African market he founded in 1962 sold every kind of African ware, like ileke waist beads; geles, or head wraps; drums; and dashikis — loose-fitting tops, which he made himself.

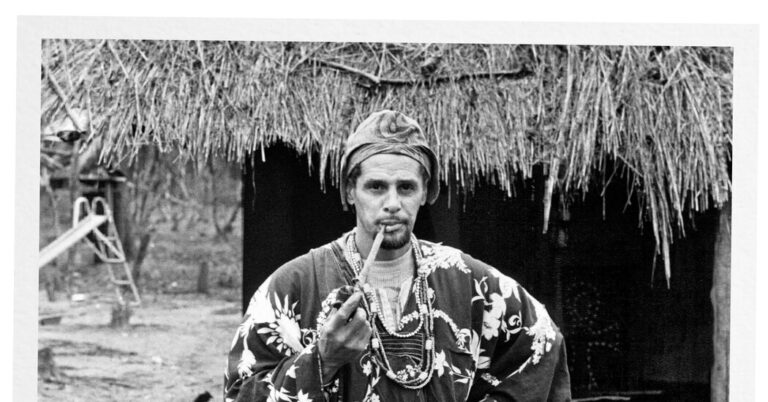

Dressed in a flowing robe, Adefunmi would preach about the cosmos and African deities from a soap box on 125th Street in Harlem. Visitors to the 1964 World’s Fair may have seen him drumming in the African pavilion. Anyone who tuned in to watch the 1977 television mini-series “Roots” saw Oyotunji residents dancing in a scene that Adefunmi produced.

In 1996, The Miami Herald called him the “father of the Yoruban cultural restoration movement.” He was ultimately crowned Oba, or King of the Yoruba in North America, by the ooni, the spiritual leader of the Yoruba people in Nigeria.

Walter Eugene King was born on Oct. 5, 1928, in Detroit to a Baptist family, one of five children. His mother, Wilhelmina Hamilton, worked for the Works Progress Administration, the New Deal agency. His father, Roy King, owned and operated a furniture reupholstery and moving company. They were followers of the Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey and were committed to his Back to Africa movement. But Walter was more interested in learning about Africa’s cultures and religions than emigrating there.

By the time Walter graduated from Cass Technical High school, he had stopped going to church. At 20, he joined the Katherine Dunham Dance Company in New York. Dunham’s performances often included songs to the orisa, Yoruba deities, and the company performed in places like Egypt and Haiti.

The Yoruba Temple in Harlem, which Adefunmi established in 1960, attracted Black activists, like the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka and Queen Mother Moore. The three served together in the Republic of New Africa, a Black nationalist organization formed on the idea that a self-governed Black nation should be created out of five Southern states. The group also sought reparations of $4 billion.

“He was a territorial nationalist,” Hucks said, “and really wanted to know, How do we build a nation for ourselves in this country?”

The answer was Oyotunji Village, the South Carolina community that Adefunmi established in 1970 as “a place of rehabilitation for African Americans in search of their spiritual and cultural identity,” he told Essence magazine. The name refers to the African Yoruba kingdom of Oyo and means “Oyo rises again.”

Adefunmi chose a rural location in Sheldon, in the heart of the Gullah Geechee Corridor, where descendants of enslaved West Africans retained their Indigenous traditions in the remote sea islands dotting the southeastern Atlantic coast.

A sign posted in both Yoruba and English welcomes visitors to the village: “You are leaving the United States. You are entering Yoruba Kingdom … Welcome to Our Land!”

Walking through the village, replete with life-size carvings and shrines, “you see the magnificence of the buildings,” Kamari Clarke, author of “Mapping Yoruba Networks: Power and Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities” (2004), said in an interview.

“You would hear the roosters crowing in the mornings,” she added, and see “people walking just in their lappas wrapped around them to go and get water, and only the Yoruba spoken.”

Clarke lived at Oyotunji and traveled with its community members to Nigeria. Its evolution from a Black-only space to a site of pilgrimage and learning open to all is one of the things that has sustained it, she said.

When Adefunmi’s son Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II went to public school, before the village established its own, he was sometimes ridiculed for his African clothing and tribal markings.

“We lived in two different worlds,” the younger Adefunmi said. “We would say, ‘Why can’t we just be regular?’ Our parents would tell us we’re not regular.”

It was ordained at his birth that he would be the next king of their village, which Adefunmi II said “was a terrible thought my whole life — I wanted to be a rapper.”

He was appointed the new oba of the village after his father died of heart disease on Feb. 11, 2005. He was 76.

Adefunmi II estimated that Oyotunji receives about 20,000 visitors annually. He said Yoruba’s growing popularity has changed his view of the village and its importance.

“Everybody’s practicing Yoruba culture today,” he said. “I can hear the language that people laughed at us for talking back in Savannah when we were kids. I can hear it on Spotify. I hear it all over the radio,” through artists like India Arie, Future and Beyoncé.

“That makes us proud,” he added. “All of this is the residual effect of what our elders did and what my father did.”

This article will appear in a new book, “Overlooked,” a compilation of 66 obituaries out this fall.