When studying Spanish, even after getting down cognates and homophones, nailing the grammar rules and getting closer to a native-like accent, there are still some simple words that can be easily confused.

These pairs of words sound quite similar, often varying by only one vowel or consonant, but they mean very different things.

To address this confusion, I’ve put together this handy post that covers 10 main Spanish word pairs that often confuse people, so hopefully, you’ll never be confused again—at least by these 20 words.

Contents

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Confusing Spanish Word Pairs

1. Mierda

(Excrement) and Miedo

(Fear)

Despite their similar pronunciation, it does help, of course, that these two words will generally be used in completely different contexts. Try to avoid using mierda in your everyday conversations as much as you can, though, as the word can come off as vulgar or rude.

Here are some examples of these words in use:

El niño manchó el pañal de mierda. (The baby stained the diaper with sh*t.)

Esta comida es una mierda. (This food sucks.)

Me dan miedo las películas de Freddy Krueger. (I find Freddy Krueger films scary.)

Solo una cosa vuelve un sueño imposible: el miedo a fracasar. (Only one thing can destroy a dream: the fear of failure.)

2. Pulpo

(Octopus) and Pulpa

(Pulp)

I was in Southern Spain in the coastal town of Huelva. I had acquired a decent level of Spanish by that time, and I was terribly sick, so I decided to buy some orange juice from the corner store.

“I need one with pulp” I thought. Then, “Oh wait,” I thought nervously, “How do I say pulp? I should have brought my dictionary.”

I walked up to the shopkeeper and said, “Señor, busco zumo de naranja que tenga pulpo” (Sir, I’m looking for orange juice that contains octopus). Despite using the subjunctive tense correctly in “que tenga,” I screwed up the noun pretty badly.

He gave me a cheeky smile and responded in typical Andalusian fashion “Bueno, zumo sí tenemos pero tendrás que ir al mar para el pulpo” (Well, we have orange juice, but you’ll have to the go looking in the sea for the octopus).

When I heard the word mar (sea/ocean), I was immediately clued in that I was, in fact, talking about octopus. My pulp was very lejos (far) from my reach.

These two should be fairly easy to remember, since octopus starts with O and pulpo ends in O.

Look at these example sentences:

Me gusta el pulpo a la parrilla. (I like grilled octopus.)

El pulpo tiene ocho brazos con los cuales nada. (Octopus have eight legs with which they swim.)

Prefiero el zumo con pulpa. (I prefer orange juice with pulp)

La pulpa gruesa da un sabor distinto a los zumos. (Thick pulp adds a particular flavor to juice.)

3. Agujeros

(Holes) and Agujetas

(Sore Muscles)

The Spanish language has a curious way to express the feeling of pain following any form of physical activity. In Spain, the word agujetas means soreness, stiffness or muscle pain.

The word can also mean “shoelaces” (in Spain and Mexico) and “knitting needles,” which is used in several Latin American countries, so watch out for those, too.

Check out these examples of these words in use:

Mi bolso tiene agujeros. (There are holes in my bag.)

Hago agujeros en la arena para que salgan burbujas de agua. (I make holes in the sand so that water bubbles pop up.)

Me gusta montar a caballo pero siempre tengo agujetas después. (I like to go horseback riding but I’m always stiff afterwards.)

Es probable que te salgan agujetas si vas al gimnasio después de no haber ido por mucho tiempo (You’d probably get muscle pain if you go to the gym after not having gone for a while.)

Mi abuela me hace vestidos con su aguja de punto (My grandmother makes me dresses with her knitting needle.)

4. Pelas

(Money) and Pelos

(Hair)

Across the Spanish-speaking world, there are many informal words to say cash money. Plata is common in Latin America, whereas pasta is the equivalent in Spain, but there are also regional variations.

In Madrid, the word pelas is often used for money between friends when casually talking about lending each other some cash. Let’s make sure not to confuse this with pelos (hair), because no one wants to lend or pay with anyone’s hair.

Here are a few examples:

¿Tienes pelas? (Do you have money?)

¿Me dejas pelas? (Can you lend me some cash?)

No tienes ni un pelo (You don’t have any hair.)

Los pelos de mis piernas son largos (My leg hair is long.)

5. Cocer

(to Boil) and Coser

(to Sew)

This word pair is tricky because depending on the country and region you are living or traveling in, the verbs cocer (to boil) and coser (to sew) are pronounced exactly the same and both used in domestic contexts.

In Latin America and some parts of Southern Spain, there is no sound distinction made between the letters S and C. For instance, let’s say you are talking with a friend over the phone and they tell you,“Estoy cosiendo.” In these locations, you could easily assume that they are sewing, not boiling something.

Confusing? Yes. Avoidable? Depends where you are and if the person performing the action is visible.

Check out these example sentences:

Has cocido demasiado el huevo y se ha hecho muy duro. (You over-boiled the egg and it became too hard.)

Algo se está cociendo en esta oficina. (Something is brewing in this office.)

Le coso un botón a la bufanda que hago para mi novio como regalo de Navidad. (I am sewing a button onto the scarf I am knitting for my boyfriend’s Christmas present.)

No te olvides coserlo a mano. (Don’t forget to sew it by hand.)

6. Papá

(Dad) and Papa

(Potato, Pope)

This next word pair only differs by where you place the stress of the word. Papá is what young children call their father. If you’re not a young child, be sure to use the word padre instead.

If we put the stress on the first half of the word (which is what the lack of accent mark tells us to do) and it’s capitalized, we get the Spanish word for the Pope: Papa.

Also, keep in mind that lowercase papa means “potato” in Latin America (patata is “potato” in Spain), and “chips” in Spain.

Here’s that distinction in this pair of example sentences:

El Papa dio un discurso en el Vaticano. (The Pope gave a speech in the Vatican.)

Mi papá es ecuatoriano. (My daddy is Ecuadorian.)

Mi comida favorita son las papas. (My favorite food is potatoes.)

7. Caro

(Expensive) and Carro

(Car)

If you are a native English speaker, it’s very important that you learn how to roll your Rs in Spanish. After all, it’s the only difference between this word pair: caro (expensive) and carro (car).

If you’ve never been able to trill your R before, it’s a skill that can be learned. But it uses some tongue muscles that native English speakers don’t usually use, so try these methods to strengthen them.

Here are some examples with these words:

El carro que quiero comprar es negro. (The car I want to buy is black.)

Ese restaurante es muy caro. (That restaurant is very expensive.)

Tu carro es muy caro. (Your car is very expensive.)

8. Hombro

(Shoulder) and Hombre

(Man)

Yes, hombres have hombros, but they’re obviously not similar in any other way.

Here are some example sentences:

El hombro me duele bastante. (My shoulder really hurts.)

El hombre de la esquina es guapo. (That guy in the corner is good-looking.)

Cuando ese hombre tiene mucha hambre, le empieza a doler el hombro. (When that guy is really hungry his shoulder starts to hurt.)

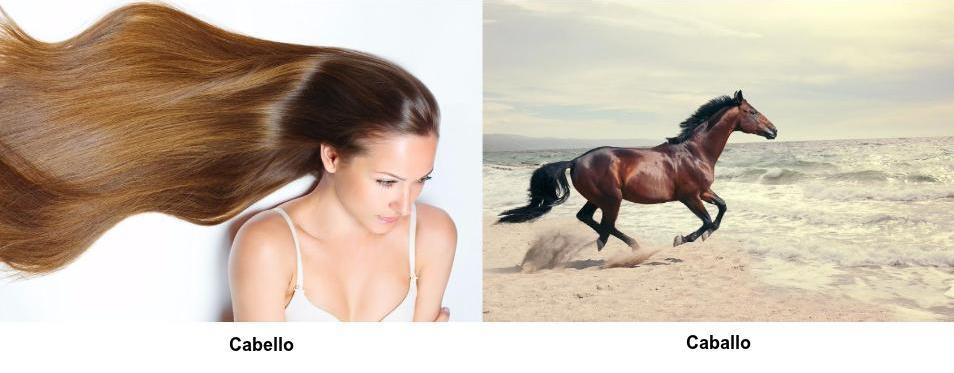

9. Cabello

(Hair) and Caballo

(Horse)

Once while I was getting ready with a friend for a night on the town in Barcelona, I blurted out “Tienes un caballo muy bonito” (You have a really nice horse). Of course there was no horse getting ready with us, so yes this was indeed another language blunder.

For the next word pair, try to associate the word bello (beautiful) with the second part of cabello (hair) in order to make sure your vocabulary doesn’t run wild.

Check out these examples:

Mi cabello es liso. (I have straight hair.)

Me gusta montar a caballo. (I like horseback riding.)

Ella se hizo una cola de caballo con el cabello. (She pulled her hair into a ponytail [lit. horse tail].)

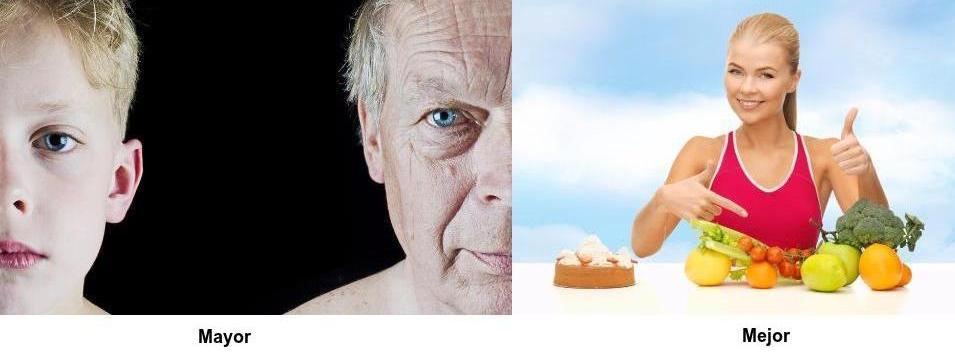

10. Mayor

(Older) and Mejor

(Better)

The last word pair is quite different in pronunciation, but can be confusing because the two words are both comparative adjectives and could easily be used in the same sentence or context.

The trick here is that mayor (older) will most often be used to describe someone’s age, whereas mejor (better) is used in comparisons with other things and people. Mayor is also the word you’d use to differentiate your older sister, hermana mayor, from your younger sister, hermana menor.

Here are some examples of these words in action:

Se le dan mejor las matemáticas a mi hermano que a mí. (My brother is better at math than I am.)

Mi abuela tiene 95 años, es bastante mayor. (My grandmother is 95 years old, she is quite old.)

Cuando sea mayor, seré mejor persona. (I will be a better person when I get older.)

My Spanish Slip-Up Story

My first exposure to Spanish was on a solo trip to Costa Rica during the summer of 2009.

I was in a crowded bar in a small port town, squished between Ticos (Costa Ricans) of varying sizes. At one point in the night, I found myself stuck beside a bizarre looking man who insisted that I try a fried pig’s ear from a small plastic bag he was holding in his left hand. “Toma…está muy rica” (Try it, it’s very delicious).

Finally I looked down to his plastic bag and noticed the little ears had little hairs sticking out of them. “Qué asco” (yuck) I thought, it was time to let this Tico know that I wasn’t interested in him or his hairy pig ears.

I looked at the man square in the eye with all the confidence in the world and blurted out, “Tengo mierda” (literally: I have sh*t). You can imagine how I felt once I realized what I had said.

The Tico man slowly put the pig’s ear away in his pocket and pointed down the halls towards the bathroom: “Allí… los baños” (The bathrooms are over there).

In case it’s not obvious, what I meant to say was “Tengo miedo” (I’m afraid). Still, I amazingly managed to scare the guy off—perhaps a language success story after all.

Go ahead, make mistakes! When you do, feel embarrassed but don’t forget to take a bow and feel proud that your slip-ups take you to the next scene, and a few steps closer to linguistic and cultural understanding.

To learn more Spanish words in context, you can try out FluentU. This app teaches you Spanish using engaging web videos from authentic native sources, like music videos, vlogs, movie trailers, new clips and more.

With the help of flashcards and interactive captions, the videos in FluentU teach you how words are used in different contexts, which helps you learn to mentally link words with their correct meanings.

Make lists, let yourself move and explore within your newly acquired vocabulary while never underestimating the value of mistakes.

¡Hasta la próxima, amigos! (Until next time friends!)

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)