In Spanish, a simple little word like a can mean many different things.

But one of the most important uses of the Spanish word a—and perhaps one of the trickiest—is the personal a.

To an English speaker, this a feels superfluous. But in Spanish, it’s very important!

In this post, you’ll learn everything you need to know about the personal a in Spanish, like when (and when not) to use it.

Contents

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

When to Use the Personal A in Spanish

When the direct object is a person or pet

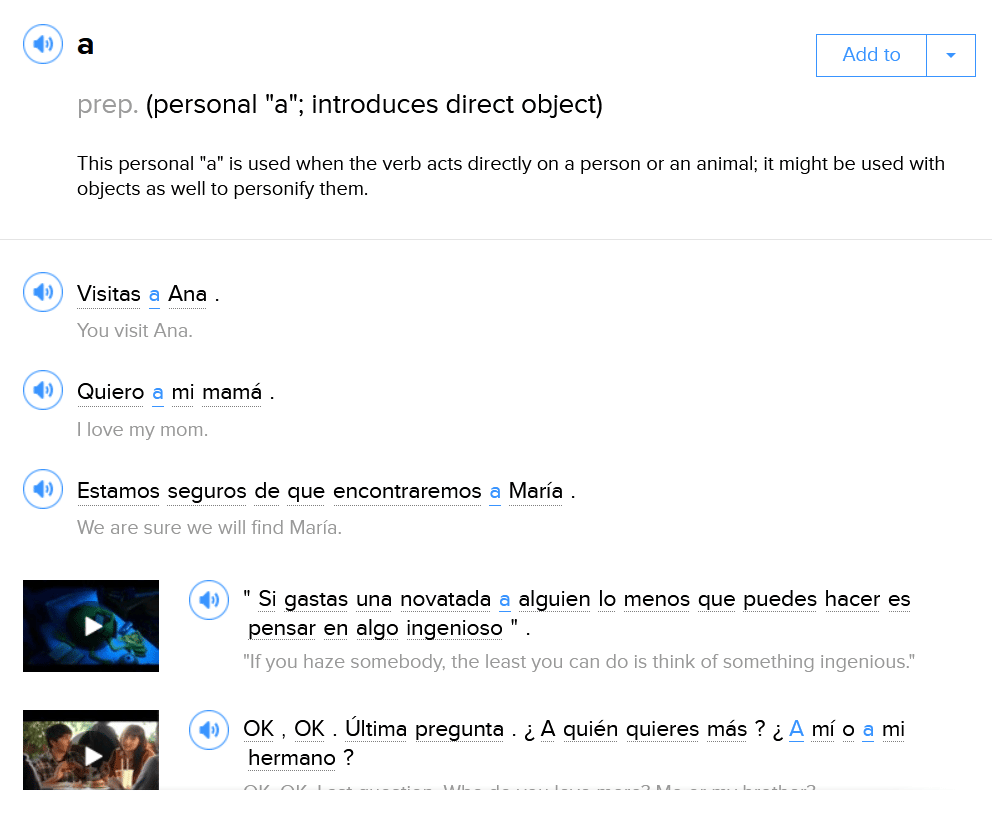

The personal a is a preposition we use when a sentence’s direct object is a person.

Confused? A simple sentence will help clarify the usage of the personal a in Spanish. Let’s take the following sentence in English:

I see Sonia.

Sonia is the direct object of the sentence. (To review, the direct object of a sentence is the “recipient” of the verb.) Since Sonia is a person, when we translate this sentence into Spanish, we would write it like this:

Yo veo a Sonia.

There’s no direct translation for the personal a into English. You simply have to remember that in Spanish, when the direct object of the sentence is a human being, you must insert an a between the verb and the direct object.

The personal a is used exactly the same whether you’re talking about one person or multiple people:

Yo veo a mis amigas. (I see my friends.)

When the direct object is a person but the person’s name or title begins with el, you can contract a + el to make al. For example:

La mujer llama al doctor. (The woman calls the [male] doctor.)

In contrast, when we use the feminine article la for a female doctor, there’s no need to form a contraction:

La mujer llama a la doctora. (The woman calls the [female] doctor.)

You can also use the personal a with a pet:

Ella llama a su perro. (She calls her dog.)

It’s important to note that the personal a is different from other usages of the preposition a in Spanish.

(As a quick refresher, a preposition is a word that links nouns and pronouns to other words in a sentence. Some examples of English prepositions would be to, on, through, about, with, etc.)

The Spanish preposition a has a few different uses. It’s often used like the English word “to.” Take the sentence Yo voy a la playa (I go to the beach). Here, we’re not using the personal a. We’re simply using the preposition a, meaning “to.”

You may also see a used with verbs like gustar and encantar, such as in the phrase:

A mí me gusta la pizza. (I like pizza.)

Check out this article on verbs like gustar for more information.

With the pronouns alguien and nadie

Alguien (someone) and nadie (no one) require the personal a because they refer to people, although no one in specific.

For example:

Yo no veo a nadie. (I don’t see anyone.)

Tienes que decirle a alguien. (You have to tell someone.)

With the question word ¿quién?

Because quién references people, you’ll need to use the personal a. For example:

¿A quién le llamaste ayer? (Who did you call yesterday?)

¿A quién viste allí? (Who did you see there?)

When Not to Use the Personal A in Spanish

There are a couple of exceptions to the personal a usage rule explained above. Here are a few instances when you should avoid using the personal a.

When the direct object is an animal

Generally speaking, it’s unnecessary to use the personal a when the direct object of the sentence is an animal.

For example, the sentence “I hear a snake” would be translated with no need for a personal a:

Oigo una serpiente.

However, if the animal in question is a pet—or some other animal about whom the speaker has personal feelings—you may use the personal a, as we’ve covered above.

When the direct object is an inanimate object

This preposition is called the personal a because we only use it when referring to human beings! With any other direct object, it’s totally superfluous. Compare these two sentences:

Yo veo a una chica. (I see a girl.)

Yo veo una hamburguesa. (I see a hamburger.)

In the second sentence, since the direct object is an inanimate object (a hamburger), there’s no need for the personal a.

With the verbs tener or haber

Even if the direct object is a person, you don’t need to use the personal a if the direct object comes after the verbs tener or haber.

For example:

Yo tengo dos hermanos. (I have two brothers.)

Hay 20 estudiantes en la clase. (There are twenty students in the class.)

How to Practice the Personal A

1. Listen to native speakers.

If you spend enough time listening to the speech tendencies of native Spanish speakers, the personal a will begin to sound natural to you, too.

- Immerse yourself in Spanish. Consider setting up an online language exchange, find an entertaining TV show in Spanish or—my personal favorite—tune in to a daily Spanish radio show and listen along.

- Use an immersion program. To listen to native speakers in various types of authentic, everyday content—such as music videos, commercials and inspiring talks—you can also use FluentU. FluentU lets you easily spot the personal a in the interactive subtitles of each video. You can also search for it to see a flashcard and other videos where it’s used in context.

- Have in-person language exchanges. Two of my favorite free resources for finding local conversation partners are Meetup—which can help you find Spanish exchange groups in your area—and Conversation Exchange, which can help you connect with other language learners for one-on-one practice.

2. Practice online.

StudySpanish.com features four quizzes on the personal a.

If you still want more practice, you can check out this quiz on 123TeachMe.com.

Or maybe you’re more of an audio learner. The Spanish Dude has a great video on the personal a, which comes with a worksheet (and answer key!) to help you understand this grammar concept.

3. Memorize Spanish phrases.

Once you commit a Spanish saying to memory, you can use it to remind yourself about grammar concepts.

Many Spanish refranes (sayings) use the personal a.

Here are a few:

Amor no respeta ley, ni obedece al rey.

(Love does not respect the law, nor does it obey the king.)

El que roba a un ladrón tiene cien años de perdón.

(He who steals from a thief has one hundred years of forgiveness.)

Haz bien sin mirar a quién.

(Do good without looking at whom.)

En las malas se conocen a los amigos.

(In bad times, friends are known.)

Un grano no hace granero, pero ayuda al compañero.

(One grain doesn’t make a granary, but it can help a friend.)

These five phrases are great examples of the usage of the personal a. If you commit them to memory, they can help you remember to add a when your direct object is a person.

Hopefully, this article has cleared up your confusion about the Spanish personal a.

Now that you’ve learned what you need to know, you’ll start noticing it everywhere—and you’ll be able to work it into your own Spanish as well!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)