The UN’s top aid official was in Saudi Arabia on Sunday for ceasefire talks between Sudan’s warring generals, as concern grows for the humanitarian situation at the start of a fourth week of gun battles and air strikes in the Sudanese capital.

Multiple truce deals have been declared, without effect, since fighting erupted between army and paramilitary forces on April 15 in the poverty-stricken country with a history of political instability.

Fierce combat since then has killed hundreds of people, most of them civilians, wounded thousands and sparked multiple warnings of a “catastrophic” humanitarian crisis.

More than 100,000 people have already fled the country.

Ahmed al-Amin, a resident of the Haj Yousif district in northeastern Khartoum, on Sunday told AFP he “saw fighter jets flying above our heads and heard the sounds of explosions and anti-aircraft” fire.

Across the Red Sea in the Saudi city of Jeddah, talks were underway aiming for a ceasefire that could push efforts to bring humanitarian aid to the besieged population.

Those unable to flee face dire shortages of water, food, medicines and other staples.

Even before the war began about one-third of Sudan’s people required humanitarian assistance, the UN said.

The fighting has seen aid workers killed, health facilities attacked, and the UN projects that the number of “acutely food insecure people” in Sudan could increase by between two and 2.5 million if the war is prolonged.

Analysts expect that it will be.

‘Gunfire everywhere’

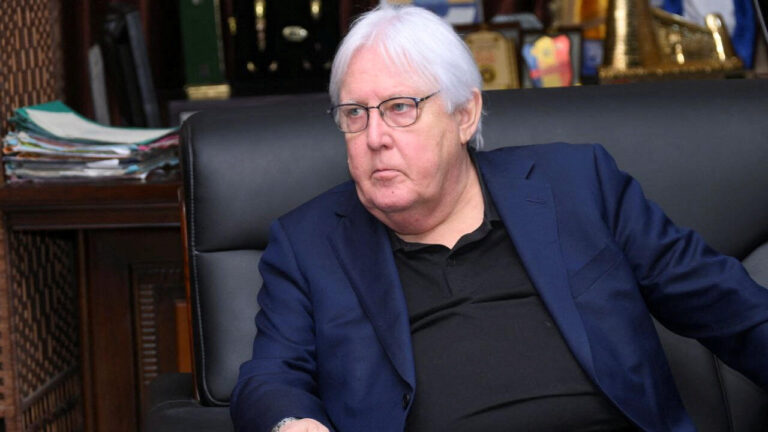

Martin Griffiths, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, was in Jeddah Sunday “and the purpose of his visit is to engage in humanitarian issues related to Sudan,” spokesperson Eri Kaneko said.

In Port Sudan last week, Griffiths said he had been informed by the UN’s World Food Programme that six trucks bringing aid to the Darfur region had been “looted en route”.

He called for security guarantees “clearly given by militaries, to protect humanitarian systems to deliver”.

There was no indication that Griffiths would play a direct role in the Saudi discussions about a possible ceasefire.

The generals leading the warring parties have said little about the talks being held in Jeddah since Saturday.

On Thursday US President Joe Biden signed an executive order that broadens authority to impose sanctions over Sudan’s conflict. It did not name potential targets.

Army spokesman Brigadier General Nabil Abdalla said the Jeddah talks were on how a truce “can be correctly implemented to serve the humanitarian side”, while Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, who heads the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries, only said on Twitter that he welcomed the technical discussions.

Riyadh and Washington have supported the “pre-negotiation talks” and urged the belligerents to “get actively involved”.

Arab League Secretary General Ahmed Aboul Gheit expressed his support Sunday for the “indirect negotiations” in order to prevent “an escalation of the current conflict” into a prolonged war “that divides Sudan into warring regions.”

At the same meeting of the bloc in Cairo, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry warned of “a slide into a worse and more dangerous security situation” affecting the region.

Heavyweights in the pan-Arab bloc are divided on Sudan. Egypt solidly supports the regular army led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the UAE is in favour of the RSF, according to experts.

Egypt, to which more than 60,000 refugees have fled, announced Shoukry will head Monday to South Sudan and Chad, both of which also border Sudan and have themselves received tens of thousands of people escaping the war.

Thousands have also crossed into neighbouring Ethiopia, most of them third-country nationals.

“This is my second war that I flee,” Syrian refugee Salam Kanhoush told AFP at the Ethiopian border town of Metema.

Women carrying infants and donkey carts laden with baggage converge on the bustling, dusty crossing.

“Our safety and life comes first,” Eritrean refugee Sara told AFP, asking to be identified only by her first name. “We can’t be thinking of the things that we have left behind” in Sudan.

The one thing they were relieved to abandon was the violence. Muhammad Yusuf, a Sudanese refugee, described “gunfire everywhere” and “expecting to be a victim at anytime.”

‘No apparent consensus’

Hopes for international efforts to silence the guns are modest.

“The lowest common denominator of the international community is a cessation of hostilities,” said Sudan researcher Aly Verjee at Sweden’s University of Gothenburg. “But there is no apparent consensus on what to do beyond that initial objective.”

Burhan and Daglo jointly staged Sudan’s latest coup in 2021.

That putsch derailed a transition to democracy after the ouster two years earlier of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir following mass pro-democracy protests.

Bashir had unleashed the Janjaweed militia in response to an uprising in Sudan’s Darfur region in 2003, leading to war crimes charges against him and others.

The RSF are descended from the Janjaweed.

Since their coup, Burhan and Daglo have fallen out in a bitter power struggle, lastly over a plan to integrate the RSF into the army.

At least 700 people have been killed in the fighting, which has spread beyond Khartoum to Darfur and elsewhere, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. The Sudanese doctors’ union said 479 of the dead were civilians.

(AFP)