My son is trilingual: he speaks English, Arabic, and Urdu. That’s a pretty cool super power. Passing it on hasn’t always been easy, especially living in the United States where we don’t need to speak other languages. This article lays out some tricks and challenges I’ve faced teaching Arabic (not to leave out my wife, but I don’t want to be putting words in her mouth).

My son is trilingual: he speaks English, Arabic, and Urdu. That’s a pretty cool super power. Passing it on hasn’t always been easy, especially living in the United States where we don’t need to speak other languages. This article lays out some tricks and challenges I’ve faced teaching Arabic (not to leave out my wife, but I don’t want to be putting words in her mouth).

But I’ll start with a key idea: our son speaks these languages because he loves us, and he sees the languages as expressions of us. This isn’t to say that the practical points aren’t important. Without some structure and approach to sharing Arabic and Urdu with our son, we would have frustrated ourselves and our son and possibly even given up.

The earlier, “easier” years

Teaching Arabic was easier during the first few years because all I had to do was interact with him in Arabic. When we’d go for walks, I’d talk to him about the animals, the trees, the sound of the wind, the people and cars passing by, anything that came to mind. He would listen attentively, sometimes jabbering back.

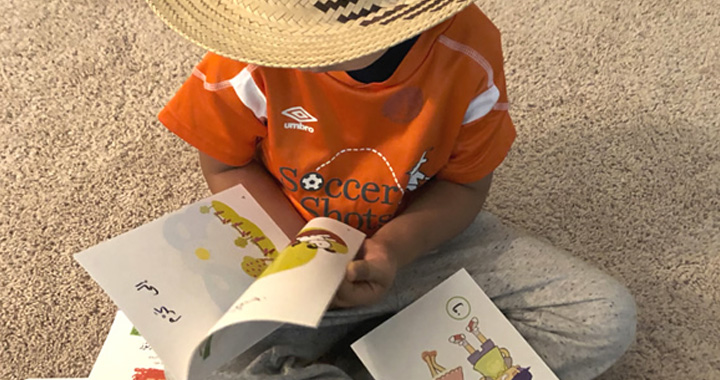

I also read a lot to him. It was a challenge to have to find and pick out and buy Arabic books for him. The lack of resources was and remains the biggest issue. First, being in the United States, there weren’t a lot of places to buy kids Arabic books. On this point, I was lucky that I ended up working with one of the founders of the online shop Maktabatee for Arabic kids books, but it still didn’t stop me from coming back from Lebanon with a whole bag of books. Second, kids Arabic books are almost all written in what is called Classical or Standard Arabic (al-Fusha), but I was trying to build up a basis in spoken Arabic before moving to Standard Arabic. Linguistic studies suggest that, in cases of diglossic languages like Arabic, making sure a child has a solid basis in the everyday, spoken language will strengthen literacy in both the everyday language and the formal language.

It was clear right off the bat that most kids books, being in Standard Arabic, used words that weren’t part of our everyday vocabulary, to say nothing of pronunciation and grammatical differences. So I started translating (Classical) Arabic books into (Levantine) Arabic. At first, I had to make notes in the books, writing in the margins so I wouldn’t forget what I was supposed to say, especially at night when I was ready to doze off faster than the little man. But over time I got better and was able to read the books smoothly; this summer I managed to read James and the Giant Peach to him, translating the entire time on the fly.

It still wasn’t enough, though. So I translated some English books into spoken Arabic. On this point, I’m eternally grateful to some Syrian friends who pitched in and helped with the translations, such as this rocking version of Abiyoyo. My dictionary work has given me a huge edge in this, as well, such as by helping me find rhyming pairs for this translation of Green Eggs and Ham.

I also collected songs and made up stories. My son quickly became an addict. Like most kids, at that age he liked repetition, which made it straightforward. I got a few trusty ones polished up and was good to go. When he was younger, if I fell asleep before finishing the story, he found out that he could stick his finger up my nose to wake me up.

These days, though, he likes a new story all the time. So I have to constantly be creative. I’ve found some great ones recorded online. I’ve also told my son classic folktales in Arabic and English, retold books like Dracula, and, as I scrape the bottom of the barrel, I pull from video games I played as a kid and just make stuff up. We’ve also started a game we call haki fadi, meaning nonsense, where we try to outdo the other in telling silly, outlandish stories.

Two tricks I learned at this age are worth mentioning. The first is repeating back what my son said in correct Arabic and in a way by which he didn’t feel embarrassed. It has now become natural for us to be in autocorrect mode, even in the middle of a temper tantrum, where pausing to correct a word is a seamless part of the breakdown over not getting to (watch more TV, spend more time at the park, or whatever the latest deal breaker is).

Second, I taught him to ask questions about Arabic when he doesn’t understand. When translating his cartoons to me, he doesn’t hesitate to ask me how to say new words he heard in English in Arabic. If he ever decides to go into translation and interpretation, he’ll have a natural basis for it.

Those were the “easy” years because the language was simple and I didn’t have to deal with the challenges posed by mainstream Arabic education. I learned Arabic side-by-side with my son, learning the names of animals, making up names for things that my Arabic teachers didn’t even have names for, teaching my son in a natural way key grammatical structures and normalizing the idea that English and Arabic can operate side by side.

Growing up and growing challenges

As my son has grown, the challenges have grown, too. This last year has really set a new bar and meeting it will require creativity and innovation. Like most parents riding the pandemic wave, I can’t help but feel overwhelmed with the lack of time and energy I feel most days; however, when I step back and look at it, these challenges are surmountable.

There is an overwhelming amount of resources and material available in English when compared with Arabic. Books are getting longer and even if I can translate them on the fly they aren’t written in Arabic so he’s not getting exposed to the written language as much. I’ve gotten some basic books in Standard Arabic that I use to teach him his letters and basic reading, but the differences with Levantine Arabic remain an issue and will only grow as books become more complex.

TV shows are also not available in Levantine Arabic. Some shows and movies have been translated into Standard Arabic and, less often, Egyptian Arabic; however, the majority of the translations in Standard Arabic are, simply put, boring, uncreative, and not understandable to kids. This particularly stands out in the age of COVID-19, when, like many parents, we’ve had to increase screen time in order to survive. Whereas before we tried to limit screen time to 20 minutes in Arabic and 20 minutes in Urdu, now it’s simply put the boy in front of a show to get through our meetings. Netflix has shows translated in Standard Arabic, but they aren’t available in the United States (unless using a VPN), and my son doesn’t like them because he doesn’t understand them. At least in Urdu, particularly because of its closeness to Hindi, there are shows available on Youtube.

I try to find a positive angle to it, mainly by having my son talk to me about the shows in Arabic. Thankfully, there are online synopses for me to read in five minutes so that I can engage with him on his shows, although he always wonders how I know what happens in every show he watches.

Another challenge is dealing with mainstream “Arabic” education. I put this in quotes because here in the United States it’s mainly Islamic education with a little bit of Arabic; it’s focused on having kids memorize religious texts without really understanding them, with less attention to teaching actual Arabic, even Standard Arabic. What is taught of Arabic tends to be grammar focused and remains alien for kids coming from a native speaking household that uses a dialect at home. My son, for the 2018-2019 school year, was in a private school that had such classes, and they haven’t changed much from when I was a kid and had to go through them. My biggest concern is that these classes will do to my son what they did to me: make him hate Arabic.

To work with this challenge, I try to focus on the similarities between Standard Arabic and what we speak at home. I encourage my son to think of Standard Arabic as a different version or dialect of Arabic, an idea that he is already familiar with since he’s been exposed to other dialects through my friends, music, and some television shows. It has become something of a game with him, asking me how they say different words in each dialect. He knows random words in dialects like Tunisian, and has started to get the idea of imitating a rural “fallahi” accent. In essence, I leveled the ideological playing field with Standard Arabic, which helps me teach my son how to control and switch between how we speak at home and Standard Arabic. Some, reading the above, might think that I’m against Standard Arabic. I’m not, and in fact I want my son to know Standard Arabic and be literate in it, but I also want him to be able to speak and interact like a native speaker.

The last challenge is the negative mindset held by many Arabs. I’ve had Arab parents tell me things like l shouldn’t try so hard, that Arabic will always be my son’s second language (I’ve actually spoken to my son exclusively in Arabic since he was born), that it’s too difficult to teach Arabic on top of the rest of the curriculum here. Despite me being only half Lebanese, my son still speaks Arabic fluently with me, and his knowledge of animals is actually better than most native speakers. In fact, our learning experience has given me something to share with others who are trying to do the same. The biggest challenges have to do with the lack of resources and people’s attitudes, not with the Arabic language itself being difficult.

A lot of people express surprise that a half-Lebanese who grew up in the United States primarily speaking English would expend such effort to pass on Arabic to his son. A language is more than just a set of grammatical rules or the ability to speak. It’s an expression of ourselves, our cultures, and our relationships. I’m trying to pass on the ability to learn about others through their language and even the ability to learn other languages. I’m trying to show my son that he can be proud of his mixed background and even share it with others. By passing on Arabic, I’m trying to pass on love for all of that.