“This”, says the Ghanaian writer Fatima Derby, “is what solidarity looks like.” After the west African premiere of Voices, a new performance project by black women, Derby was one of many at the event in Accra, Ghana who were of the same mind. “It’s a huge defining moment,” she says.

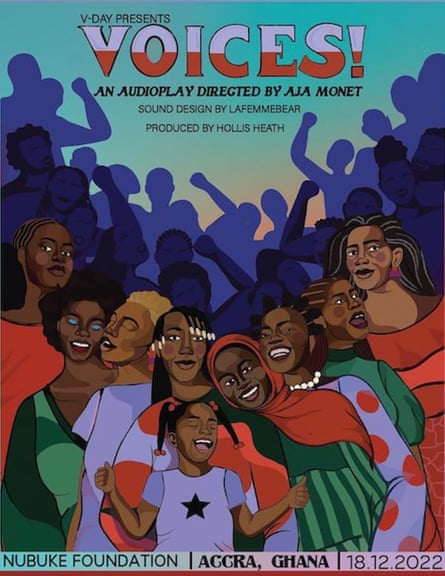

Voices, an audioplay and campaign exploring the stories of black women in Africa and in the diaspora, was launched on 18 December at the Nubuke foundation in Accra.

The play, directed by the poet and activist Aja Monet, was curated by V-Day, a global movement working to end violence against women, which uses art and activism to influence culture and policy change. The group’s founder, US playwright V (formerly Eve Ensler), best known for her seminal play The Vagina Monologues, was present, together with figures from Africa and the diaspora including the academic, leftwing activist and author Angela Davis, the US actor Rosario Dawson, and the Ghanaian feminist Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, the author of The Sex Lives of African Women.

The immersive sound event had been in the pipeline for just over a year, and featured works in the common V-Day theme of anti-violence against women of all identities.

Mars Storm Rucker’s performance Call Me Sir, for instance, explored what it is like for a trans person living with gender dysphoria. In a journal-style monologue, Rucker drew the audience in as they navigated troubled relationships with themselves and their loved ones.

“The voice is such a powerful tool,” says Monet. “Many people are encouraged to speak, but not enough people are being encouraged to listen.”

Voices is designed to encourage women to listen more deeply to experiences of other women. Monet and her co-creators, the musical artist LeahAnn Mitchell, AKA Lafemmebear, and the actor and playwright Hollis Heath, opted to go with an audio-only performance specifically to encourage “active listening”.

Davis, who has become an icon for black feminists, admits she has often felt conflicted about invitations to lead events in countries that possess strong grassroots feminist movements, and believes it is “important to adopt a posture of learning, rather than leadership”.

The activist – a former member of the Black Panthers and the Communist Party USA – says that after she released her book Women, Race and Class in 1981, people started to refer to her as a feminist. But by then, she didn’t identify as one and preferred to describe herself instead as a “black revolutionary”, not feeling there was a place for her politics in the mainstream feminist movement, which was largely defined by a white middle class at the time.

But “feminism has changed”, she says, and she is herself one of the most powerful voices on intersectional feminism – an approach that recognises how various forms of oppression, including race, imperialism, gender and sexual identity, can compound women’s experiences with discrimination.

V-Day has traditionally run campaigns to organise women around anti-violence, body positivity and sexual expression. Inspired by V’s Vagina Monologues, it began 25 years ago, and has since raised $120m (£100m) in support of grassroots groups.

Although the Vagina Monologues, written in 1996, will continue to occupy an important place in the anti-violence movement, plans were announced two years ago to bring on board a wider range of artistic works such as Voices, made by communities V says have not been heard “the way white voices are heard”.

V says: “What’s different about these stories is that black women are telling them through their only lens. There’s no monolith, there’s no one story – the stories are vast, intricate and complex. They are specific, yet universal.”

A hard listen was Tyshawna Maddox’s My Rapist soliloquy, which explored a survivor’s dark ties to their abuser, through themes of power, control, inner conflict and silence.

“It was really intense to listen to,” says Afia Anim, 28, a Ghanaian-Dutch audience member at the event. “But I found it important as well, because that’s the reality of so many women I know. How is it that almost all the women I know have dealt with assault, harassment or rape? It needs to stop.”

Movements such as #MeToo, that swept much of the world, struggled to gather momentum across Africa, despite high rates of sexual violence and harassment in some countries. South Africa, for instance, has one of the highest rates of rape in the world – with roughly 115 incidents a day recorded in the year 2019-20. Yet organisers say that even with such numbers, the country’s government remains oddly lax.

“The situation compels me to keep speaking out,” said Lucinda Evans, South Africa’s coordinator of V-Day’s One Billion Rising mass action. “We are not tapping out.”

Another Voices performance focused on sexual expression. Zonya Johnson’s Sex and Flying had the audience listen in to an intimate call between friends, where one described a sexual encounter with a new partner, in which she voiced her sexual desires using flight metaphors – pushing aside long-held reservations.

Sekyiamah says that conversations about sex on the continent remain limited and are centred around male pleasure, heterosexual relationships, child-bearing or safe sex.

“Many of us weren’t told anything about sex growing up,” she says. “We were not told that sexuality is on a spectrum, and there was no room for you to think about sex as something for pleasure.”

Sexual expressions by queer women on the continent, in particular, are suffocated by religious fundamentalism, she says, pointing to an anti-LGBTQ+ bill introduced in Ghana’s parliament last year. If it becomes law, people identifying as queer or campaigning for LGBTQ+ rights would face prison sentences, and intersex people would be encouraged by the state to have medical intervention.

Moreau Halliburton, a 23-year-old American, says Voices is one of an increasingly narrow number of places where she and other people who are “visibly queer” can be themselves.

Voices was launched in December, a time when the country typically ramps up efforts to encourage Africans in the diaspora to visit and resettle in the country – part of its “year of return” campaign, which began in 2019. Despite a growing number of returnees, Monet says she was struck by how few spaces there are for conversation and gatherings between black women from the continent and the diaspora.

“Our respective cultures and communities are holding a lot,” says Monet, who believes that an understanding among black women of each other’s experiences is necessary for an inclusive feminist movement.

“I think we need to lean into the tension, and the contradiction and the conflict,” says Monet. “When we are uncomfortable and when we find ourselves struggling with one another, that is an opportunity to be more intimate and more thoughtful – to learn and to listen.”

Derby, who draws inspiration from Davis’s work, says the dedicated space of V is a vital starting point. “What’s important is intersectionality and understanding that our experiences, even though similar, are also different based on our proximity and relationship with power.

“All our struggles are connected.”