The search for Ojibwa classroom posters — let alone fluent language speakers — proved challenging when Riverbend Community School began to build its bilingual program.

Winnipeg teachers had to take matters into their own hands; since welcoming the first students in September 2016, almost all of the instructional material used in their elementary classrooms have been made in-house.

Now, thanks to an ambitious project in the Seven Oaks School Division, the Riverbend community and anyone else interested in the language can access beginner lessons via an online dictionary and complementary app.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Jennifer Lamoureux, Seven Oaks’ teacher team leader for Indigenous education, shows a language app. ‘There’s a generational gap in who can speak the language fluently,’ she says.

“There’s a generational gap in who can speak the language fluently,” said Jennifer Lamoureux, Seven Oaks’ teacher team leader for Indigenous education.

“So, we need to have those print resources, video resources, audio resources to be able to immerse our learners in the language and to support those at various levels of learning the language so that we can strengthen our languages, revitalize our languages, hold onto our languages.”

The collection initially consisted of placards, worksheets and books created by local teachers and elders to help students learn how to tell time, practise greetings and identify weather, among countless lessons in the language.

This year, there have been two significant additions: Giga-Ganoonidimin Miinawaa, an 118-page online dictionary named after a phrase that roughly translates to “we will talk together again,” and a free app titled They are Talking.

Seven Oaks secured a federal grant for the projects through a fund aimed at supporting community efforts to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages.

Anishinaabe teacher Pamela Morrison, who self-identifies as being “fluent enough to get by,” said she feels immense pride while collaborating on resources that reinforce a language that colonists could not eradicate.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Lamoureux, Seven Oaks’ teacher team leader for Indigenous education, holds the Anishinaabemowin dictionary at Riverbend Community School in Winnipeg.

Indigenous students were discouraged, often by violent means, from speaking their mother tongue when they were removed from their families and placed in the residential school system.

“This is the way that we’re rewriting our own future… I just love hearing (kids speak Anishinaabemowin). It’s like self actualization – being able to be in a place where you can hear your whole language,” said Morrison, who works at Riverbend.

A team of teachers, elders and fluent language speakers in Winnipeg started exchanging ideas for their introductory dictionary, a publication designed with young users in mind, in the spring of 2021. It took about 12 months before an edition was made available for every Ojibwa classroom.

The final glossary is composed of more than 500 words and phrases, from animal names to emotions, grocery items to questions about families. There is a detailed explanation about the double-vowel writing system and vowel sound chart.

As a nod to the oral history of the language and to accompany the dictionary’s pronunciation guide, a newly released app features related audio clips recorded by Riverbend staff and students.

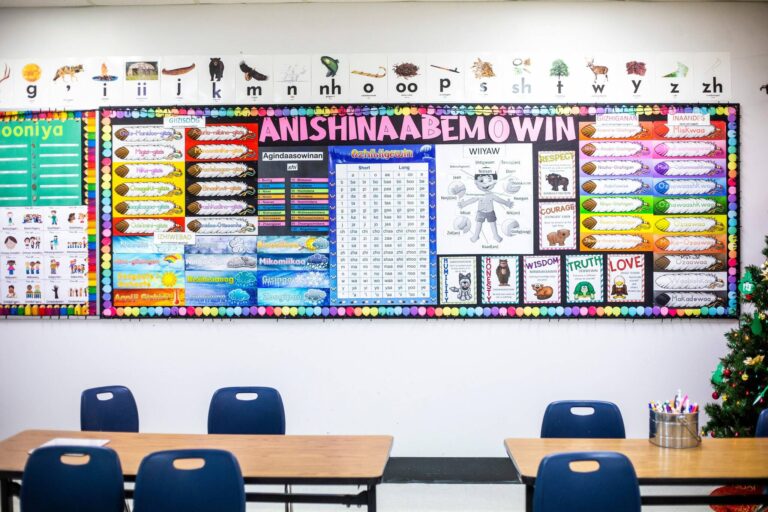

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Ojibwa language posters at Riverbend Community School. Since welcoming the first students in September 2016, almost all of the instructional material used in their elementary classrooms have been made in-house.

Teachers indicated there was much discussion to determine which phrases should be used in the resources, given many of the community members involved hail from different Ojibwa nations that have their own unique dialects.

In some cases, new terms were coined for modern technologies. For example, a water fountain is now known as nibi gaa-minikweng (the place where you drink water) in Seven Oaks, by drawing on the descriptive nature of the language.

Ultimately, the educators deferred to local pronunciations and Mary Courchene, a career teacher who is currently an elder-in-residence in the division.

Courchene said it is a “full circle moment” every time she hears her great-grandchildren, who are enrolled in the program, share their newfound vocabulary — including counting up to 100 and beyond — because of her starkly different experience at their age.

“We want our children to be proud of who they are,” said Courchene, who is a member of Sagkeeng First Nation and survivor of Fort Alexander Residential School.

Approximately 100 K-5 pupils are enrolled in the specialty program and there is a waitlist for entry due to classes being capped at 15 in order to fully immerse participants in language and cultural activities.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Ojibwa language activities (this one exploring the bison teaching of respect) at Riverbend Community School in Winnipeg.

Run by Ojibwa role models who constantly expose young children to their language and culture, the program has turned Indigenous education into a model for learning rather than simply a subject, said the principal of the elementary school.

“It’s so much more than a program,” school leader Ross Meacham said. “The real work is in the growing of these young, powerful lives, richly embedded in their culture.”

The team leader, who oversaw the creation of new resources, indicated they were made with the elementary community in mind, but she acknowledged how significant this project is for the wider Anishinaabe world.

“I hope that anybody interested in learning Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwa) will access these materials and be supported with them. I use the dictionary all the time,” added Lamoureux, who is Ojibwa and Cree, and takes weekend language classes.

It was only 10 years ago when the University of Minnesota created a virtual Ojibwa-English dictionary, a first-of-its-kind online resource that continues to expand with new terms primarily from First Nations across the Prairies and midwestern U.S.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS An Ojibwa label saying ‘hello children’ on a door at Riverbend Community School.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Ojibwe Language Dictionary