In the Southwest, Indigenous people were held in bondage even after the Civil War — a hidden history with lasting scars

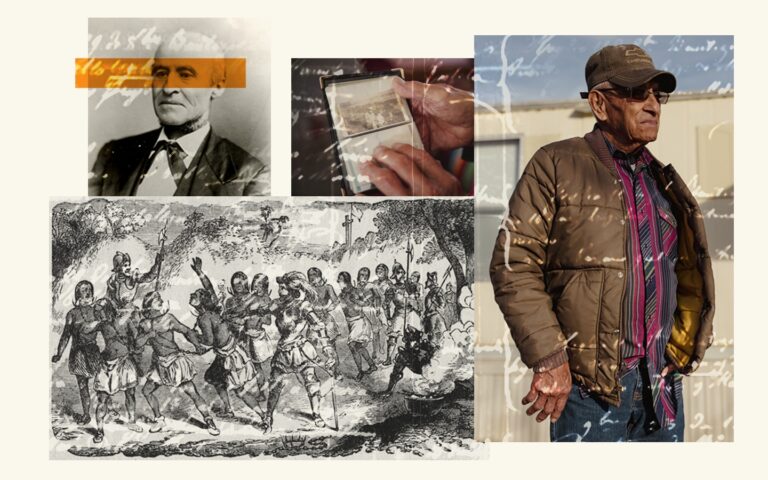

“Dad never talked about slavery,” Carlos said, though his own life has been shaped, in part, by that hidden history.

Carlos had always been told that his grandfather was Navajo, but had somehow lost his membership in the tribe. He knew his grandfather’s early life had been hard, violent even. He knew what his grandfather passed down to his father and then his father passed down to him: a heritage of hard work and profound disconnection.

It was Bobby, not Carlos, who yearned to know more. Bobby, now 60, peppered Carlos and Carlos’s late father, Preciliano, with one question after another.

“Sometimes you wonder where you come from. A lot of people tell you, ‘Oh, you look Indian,’” Bobby explained.

At last, Bobby and other relatives turned to a New Mexico genealogist, who showed them the handwritten documents that revealed who they are. An enslaver’s records, showing the 1864 baptism of a boy who was stolen from his tribe and held in captivity.

That boy was Carlos’s grandfather, Alejandro Gallegos.

And the men who enslaved that boy held great influence, far beyond the power they had over Alejandro’s childhood.

Younger relatives asked Carlos: Did you know your grandfather was enslaved by the family of a congressman? He tried to summon details from his memory without much success. His grandfather had died before he was born.

Carlos is 82 now. He’s still sounding out that Spanish word, genizaro, and understanding its double meaning. Because that term isn’t just a word for his grandfather and all the other Native Americans who were enslaved. It’s a word used to describe their descendants, like him, who are still marked by that slavery.

Enslaved after slavery’s end

Alejandro Gallegos was born in 1855 with a different, Navajo name that has been lost to history. He was about 9 years old when he was kidnapped from his family — probably by a rival tribe — and sold into slavery. In 1864, Alejandro was baptized, renamed, and taught to herd sheep, a task he labored at without pay well into adulthood.

As one of thousands of Indigenous people who were enslaved by Spanish colonizers in what is now New Mexico, Alejandro’s bondage placed him in a unique circumstance in history. He was enslaved even after the Civil War, when slavery became unconstitutional in the United States. And the family that owned the hacienda where Alejandro worked sent one of New Mexico’s first delegates to Congress.

Three of New Mexico’s earliest delegates to Congress were slaveholders. When New Mexico became a U.S. territory and these men went to Congress, they joined a body where many of their new colleagues were slaveholders , too.

As part of an investigation into Congress’s relationship with slavery, The Washington Post has documented more than 1,800 lawmakers who were enslavers at some point in their adult lives.

While almost all of these congressmen enslaved Black people, the New Mexican lawmakers enslaved American Indians. Native Americans were also enslaved in other parts of the United States, including by future lawmakers. The Northeast Slavery Records Index recorded that Joseph Stanton Jr., who would go on to represent Rhode Island in the House and Senate, listed an unnamed Indian in his household in a local census in 1774 who researchers believe was enslaved.

A growing community of New Mexicans now recognize that their ancestors were enslaved, a part of the story of American slavery that has rarely been told.

Enslavement of genizaros was a very different institution from the centuries-long chattel slavery that shaped the African American experience. Indigenous people who were enslaved were far more likely to obtain their freedom in adulthood and to bear children who were not enslaved, among other major differences.

Even so, the legacy of genizaro enslavement runs deep.

“I’m a firm believer in genetic memory — a lot of the things these grandmothers and grandfathers have gone through, it’s passed on to us in some form or fashion,” said Miguel Torrez, a genealogist who helps New Mexicans identify their ancestors and worked with the Gallegos family. “The reality is a lot of these descendants are very traumatized. … They’re living with drug addictions, alcohol addictions.”

Other New Mexicans are focused on the persistent legal ramifications of Indigenous enslavement. Descendants are often unable to enroll in Native American tribes, meaning they cannot access medical care through the Indian Health Service or qualify for other government benefits. They have lost access to land that was once legally guaranteed to formerly enslaved genizaros and their descendants by the Spanish or Mexican government. Their claims were denied by the U.S. Senate when the land changed hands from Spanish to Mexican to American.

Those disadvantages, which genizaros in New Mexico are still fighting to rectify more than a century and a half after the end of slavery, are the product of a legal system in which the slaveholders wrote the rules.

A Spanish-speaking enslaver in Congress

The Rev. Jose Manuel Gallegos was a leading citizen in one country when it suddenly became another.

A Catholic priest, Jose Gallegos was born when New Mexico was part of Spain; became involved in Mexican politics when his home was part of an independent Mexico; and when the United States took over the territory in 1848 following the American victory in the Mexican-American War, dove into his new nation’s politics, too.

In 1853, Gallegos was sworn in as New Mexico’s second delegate to Congress, becoming the first person of Mexican descent in Congress. A White West Point alumnus (who was later killed fighting for the Confederacy) represented the new territory for one term.

Gallegos arrived in Washington unable to speak any English. When a fellow congressman requested that Gallegos be able to use an interpreter on the floor of the House, two-thirds of his new colleagues voted no. He persisted anyway in introducing legislation in a language he did not speak. Newspaper editorials poked fun of his lack of fluency.

When he ran for a second term in 1855, he narrowly won. But his opponent, Miguel Otero, challenged the results, claiming to the House Committee on Elections that Gallegos had won because Mexican citizens illegally voted in the election. Gallegos defended himself to the committee against the “sneers and jests” congressmen made about his language skills. But Otero, whose political faction was called the American Party, argued that if he were in Congress instead, he could speak “in the language of its laws and its constitution.” Members voted to seat Otero instead of Gallegos, and Gallegos went home to New Mexico in 1856.

While Gallegos was in Washington, his brother Pablo managed the family’s sprawling ranching compound near Abiquiú, according to Torrez. Upon his return, Gallegos stayed involved in politics, serving as speaker of the territorial legislature. At one point, he endured imprisonment for his support of the Union during the Civil War — despite listing 21 “servants” in his household in the 1860 census. A 2013 congressional report said that some or all of these Indigenous servants were, in fact, enslaved.

Meanwhile, Pablo enslaved three children sometime in or before 1864, baptismal records suggest. The children, including Alejandro, had likely been kidnapped from their tribes by another tribe that stole children to sell into temporary or long-lasting slavery. They were baptized as Christians and given new identities. Most took Spanish first names and the last names of their new enslavers, forgetting their given names in their native tongue.

Congress would approve the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery, one year later. But the 13th Amendment didn’t end slavery for Alejandro. So many New Mexican slaveholders refused to comply that Congress passed an 1867 law specifically aimed at dismantling “peonage” in New Mexico.

Historians have found evidence of Indigenous people who were still enslaved in New Mexican homes into the 20th century, some until their deaths.

Alejandro was still herding sheep on the Gallegos hacienda in 1870, census records show.

At the time, Jose Gallegos was preparing to run for Congress once again. The 1871 election, which Gallegos won, was so contentious that a riot broke out after one of Gallegos’s campaign speeches, leaving nine dead and 40 injured.

Jose went back to Washington. Alejandro remained in Pablo’s household, likely in violation of federal law.

His descendants aren’t sure how he became free, but they know that he finally did. The 1900 census shows Alejandro living in Coyote, about 20 miles from Abiquiú. Those 20 miles marked the distance from slavery to freedom.

In 1890, handwritten documents unearthed by a relative show Alejandro married. He had a daughter and then when he was nearly 50, a son, Preciliano, whose baptism was recorded by hand in 1903. Alejandro taught young Preciliano the shepherding trade that he learned in slavery before he died sometime after 1910.

Alejandro passed away long before Preciliano and his wife welcomed their fourth child, Carlos Gallegos – another generation to bear the name of the family that once enslaved them. Carlos grew up just down the road from the place his grandfather worked in bondage, and learned to tend the descendants of the same sheep.

A photo that Preciliano kept of Alejandro made an impression on Carlos as a child.

“You can tell he was a Navajo,” Carlos said. He remembered Alejandro sitting in what looked like a rocking chair. “I remember he got in his hand a whip or something in that photo.”

Rather than speak of Alejandro’s youth in slavery, his widow preferred to emphasize his dedication to providing for his family. “What I heard was, he was always working,” Carlos recalled.

His grandmother described Alejandro as “a good man, a good Navajo man.”

Alejandro was not, however, an enrolled member of the Navajo tribe. When genizaros were enslaved, they commonly lost their tribal communities — which means their descendants are often unable to prove their genealogy, in order to enroll in an American Indian tribe today.

“Slavery doesn’t stop when the slaves are free or they die. There’s these lingering effects,” said Bill Piatt, who discovered his family’s descent from enslaved Native Americans and now calls himself America’s only genizaro-identified law professor. He has written law review articles calling for tribal benefits for genizaro descendants. “They lost their tribal identity. They can’t point to a tribe, which means the federal government won’t recognize them, which means they aren’t eligible for benefits.”

Officials in the Navajo Nation did not respond to requests from The Washington Post to discuss what qualifications someone must show to enroll in the tribe and what the tribe’s relationship is today with descendants of people who were enslaved.

It is a question that still echoes in many Native American tribes across the country in various forms. In the Southeast United States, some Native Americans were the enslavers, not the enslaved. Descendants of Black Americans enslaved by Cherokees sought membership and were initially denied by the tribe; a federal judge ruled in 2017 that the Cherokees must allow the estimated 3,000 living descendants of those they enslaved to enroll.

Carlos has mixed feelings about the government benefits that would come with tribal enrollment. A proud American who wears a “These Colors Don’t Run” T-shirt, he believes in the self-reliance that his father and grandfather exemplified.

A wiry octogenarian in torn blue jeans, he still bounds right over his fence to greet visitors when they arrive at his trailer on a dead-end street in Farmington, the town more than 100 miles west of Coyote where he moved decades ago for the promise of oil field jobs.

“From when I was young, maybe 15, until I was 76 years old, I worked all my life,” he tells his grandchildren. He only stopped laboring as a “swamper,” setting up and taking down oil rigs, when his boss told him he had to retire from the physically demanding job in his 70s.

He doesn’t like to stay still. Neighbors in his trailer park pay him to clean their yards. He’s installing a new engine in his 1959 Chevy Apache, a truck that he notes wryly was named after people like him.

But he went to the grocery earlier this year, and he’s been thinking about it since.

“A Navajo lady working in Safeway, she tells me, ‘Where are your food stamps?’ I say I don’t have food stamps. She says, ‘How come?’”

After he retired, he and his late wife applied, and were told they’d get $25 per month, he said. “Twenty-five dollars. What are you going to buy for $25? … Probably if you were Navajo, you get more.”

While tribal affiliation might not actually change food stamps determination, tribal members do qualify for health care and other forms of assistance meant to address poverty on Indian reservations. Billboards dot the Farmington area advertising assistance for tribal members with rent, therapy and health care, abutting a gas station that flashes “Let’s Go Brandon” in electronic lights and another that says, alongside Trump posters, “I miss the America I grew up in.”

Carlos went with his stepdaughter recently to a Navajo tribal office to ask what he would need to prove to join.

The tribe’s enrollment requirements are stricter than many, including a mandate that new members prove they are at least one-quarter Navajo by ancestry. Some would-be applicants struggle to find documentation, such as affidavits or church records that prove their parents’ and grandparents’ heritage, even without a history of enslavement. Still, enrollment has surged recently: The tribe grew by nearly one-third in 2020, from 306,268 members to 399,494, when many sought the pandemic relief checks of about $1,350 per adult that the tribe distributed to members from its federal coronavirus relief aid.

When Carlos asked about enrollment, he was given the address of a different tribal office.

As he watched the sun set from his trailer porch earlier this year, he mused about whether he would give it a try. He knows it’s a long shot for someone like him — an octogenarian genizaro — to become a tribal member.

“I want to do it,” he said. “If they want to help me, fine. If they don’t, that’s fine. I do wish I knew my grandfather, but I never did. I just saw him in the picture. He really looked like a Navajo.”

And now Carlos is certain: “He was a Navajo.”

Editing by Lynda Robinson, photo editing by Mark Miller, video editing by Amber Ferguson, copy editing by Thomas Heleba, design by Michael Domine.

Abby Raskin, a Post reader who lives in Brooklyn, contributed information about Jose Manuel Gallegos that added him to The Post’s database on congressional enslavers. Nick Arjomand, a reader in Los Angeles, contributed the information on Joseph Stanton Jr.