By Diana Pang

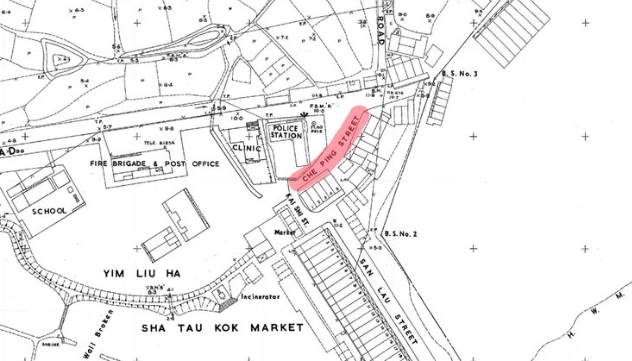

There are two different English names near Chung Ying Street (中英街, China England Street), a historical location on the Hong Kong—mainland China border. Car Park Street, a translation of the Chinese name (車坪街), can be seen on the old T-shaped sign while the newer sign reads Che Ping Street, the transliteration of the Cantonese. So what happened there?

The street was the terminus of the Kowloon–Canton Railway’s short-lived Sha Tau Kok branch in the early 20th century. Sometime after the line ceased operation in 1928, the street was renamed.

While there appears to be no records about the name change, it begs the question: why are some street names converted semantically and others phonetically?

Not that kind of junk

Street names are bilingual in Hong Kong but the conversion between English and Chinese names is often confusing. Mistranslations and ill-sounding transliterations sometimes lead to hilarity.

The Geographical Place Names Board, founded to clean up inauspicious or eyebrow-raising place names, famously rebranded the place now called Tseung Kwan O (將軍澳) in the 1980s. When the British first surveyed the area, it was named Junk Bay after the junk boats spotted nearby.

With landfills and ship-breaking operations nearby, the name caused some problems during the new town’s development as it was taken to refer to “junk” or trash. A transliteration of its Chinese name was then given to the area, renaming it Tseung Kwan O.

Despite the committee’s efforts to eradicate unfortunate-sounding names, it is unclear how Wan King Path (灣景街, waan1 ging2 gaai1, ‘Bay View Path’) in Sai Kung managed to survive the purge in the 1990s.

One way or another

In many East Asian countries such as China, South Korea, and Japan, street names are often romanised versions of their native languages. Unlike our neighbours, Hong Kong’s street names are sometimes not merely transliterations between English and Cantonese.

Some are translated (e.g. Hospital Road ↔ 醫院道) and others are a mix of transliteration and translation, often with numbers or cardinal directions (e.g. Yee Kuk West Street ↔ 醫局西街). There are also streets where their bilingual names are either mistranslated or seem to have no relation to each other (e.g. Stewart Terrace ↔ 十間, “Ten Units”).

Transliteration

Most street names in Hong Kong are transliterations between Cantonese and English. As a former British colony with fewer than five per cent of the people being primary English speakers, similar sounds are helpful for communication between races.

In a few rare cases, street names are transliterated from Chinese languages other than Cantonese. Daoyang Road (道揚道 dou6 joeng4 dou6) and Jat Min Chuen Street (乙明村街 jyut3 ming4 cyun1 gaai1) took their names from notable Chinese figures with Mandarin and Hakka names.

Several streets have transliterations that do not even sound Cantonese or Mandarin. Take a walk around the Yau Tsim Mong area and you will find many streets named after different Chinese cities. Postal Romanisation is used in some streets (e.g. Peking Street), where the transliteration is neither Cantonese- nor Mandarin-sounding. These old Chinese place names were replaced by Mandarin pinyin in the 1950s.

Linguistic differences between English and Chinese pronunciations and writing systems are evident in some transliterations. A common misreading of the silent “h” is found in Chinese transliterations of Bonham, Chatham, Wyndham, etc., where “ham” is rendered as 「咸」(haam4). In one particular case, differences in English and Chinese writing systems resulted in a unique name. A Chinese clerk accidentally transposed “Alexander Terrace,” its intended name, as Rednaxela Terrace because Chinese was written from right to left at the time. The name stuck and became a feature of Mid-Levels.

Translation

The Hong Kong government and property developers have been responsible for naming and translating street names since 1842. To no one’s surprise, translations are not always accurate. Some are partly translated, like Princess Margaret Road (公主道), where Margaret was omitted in the Chinese name. Others are downright incorrect, such as Pine Street (杉樹街) and Fir Street (松樹街), in which their Chinese translations were erroneously swapped.

Adding to the confusion are mistranslations of polysemes (words with multiple meanings). Constructed in the early 1840s, Queen’s Road was named after Queen Victoria and remains a key thoroughfare to this day. However, instead of referring to the sovereign ruler (女皇), the Chinese name was mistranslated as queen consort (皇后), the wife of a King.

Other examples of mistranslated polysemes include:

- Pound Lane (磅巷) — named after an animal shelter nearby, was mistaken for a unit of measurement

- Power Street (大強街) — named after a power station, but mistaken for strength

- Spring Garden Lane (春園街) — named after a garden with a spring fountain, but mistaken for “spring” (the season).

Nuances in the Chinese language can be spotted in some street names. “Dock” in Chinese is「船塢」 (syun4 ou3), yet the Chinese name for Dock Street (船澳街), named after the Kowloon Docks is a meaningless homophone (words with the same pronunciation but different meanings) of「船塢」(syun4 ou3).

The translation of Ice House Street into ‘Snow Factory Street’ in Chinese may seem baffling to some, but this is due to a particular nuance in Cantonese. Ice (冰) and snow (雪) were interchangeable in Cantonese. For example, refrigerator in Cantonese means ‘snow cabinet’ (雪櫃) whereas it is ‘ice box’ (冰箱) in Mandarin. Named after the building that stored ice shipped from North America in the 1840s, ice was never manufactured on Ice House Street.

Ones that bear no relations

Wishful thinking

To convey good wishes for the neighbourhoods, the government and property developers often christen streets with auspicious names in Chinese that have no linguistic relation to their English counterparts.

The Governor’s Walk, translated into “Together Happy Walk”「同樂徑, was taken from the Chinese saying「官民同樂」which means joy “shared between rulers and people.”

Mong Kok is another prime example. The former coastal region was named after the overgrown silvergrass found in the area 「芒角」(mong4 gok3, ‘corner of silvergrass’).

When the government reclaimed the bay and developed the area in the early 1900s, the Chinese name was renamed to its current appellation [旺角」(wong6 gok3) which means “Prosperity Point.” The English name was never updated. With its extremely high population density of 130,000 per square kilometre, perhaps the name did deliver.

Colonial imposition

Like other then-colonies, many places and streets in Hong Kong were named after colonial officials. Rather than being just transliterations from English, their Chinese names often tell a different story.

Known for its fishing village, not many people know that Aberdeen is the “original Hong Kong.” Named after George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, who played a pivotal role in the Opium Wars leading to the cession of Hong Kong, Aberdeen’s Chinese name 「香港仔」(hoeng1 gong2 zai2, ‘Little Hong Kong’), gave Hong Kong its name. When the British landed near Aberdeen in the early 19th century, they mistook the name of the village “Hong Kong” for that of the entire territory – and the rest was history.

Some colonial street names were decolonised even before the Handover. Jervois Street was named after British General William Jervois, who was in charge of rebuilding Sheung Wan after the devastating fire of 1851. Originally transliterated to「乍畏街」(zaa3 wai3 gaai1), 「乍畏」was considered inauspicious as it means “dread” in Chinese. The Chinese name was renamed to「蘇杭街」(sou1 hong4 gaai1, “Suzhou Hangzhou Street”) in 1978 as most of the shops along it sold textiles from Suzhou and Hangzhou.

Some colonial place names with different Chinese and English interpretations remain a mystery to this date. Whoever Penny’s Bay (竹篙灣, “Bamboo Pole Bay”) was named for would not be pleased to know that it would become a dreaded Covid quarantine facility.

Colourful highways

Some highway names have unusual origins. Rather than being named after someone called Twisk, Route Twisk (荃錦公路) came from the initials of the two places it links: Tsuen Wan (TW) and Shek Kong (SK). The origin of the ‘i’ in the middle has been contested — some claimed that it refers to “intersection” while others claimed that it was a misprint of “Route TW/SK.” In Chinese, the highway means Tsuen Wan – Kam Tin Route (Kam Tin is an area next to Shek Kong).

Hiram’s Highway (西貢公路), connecting Sai Kung to Clear Water Bay, was named after Major John Wynne-Potts who expanded the road built by the Japanese military during World War II. So, where did Hiram come from? At that time, an American tinned sausage brand called Hiram K. Potts was supplied to the British army in large quantities as military rations. The sausages were hated by everyone, but Major Wynne-Potts gladly accepted them from his colleagues in exchange for other food. Due to the brand of cans bearing his surname Potts, he became nicknamed Hiram over time. The anecdote is lost in its Chinese name as it only refers to Sai Kung Highway with no mention of said sausage.

Chef’s kisses

In spite of the numerous bizarre street name conversions, there are a few that deserve a special mention. A few streets such as Link Road (連道, lin4 dou6) and Welfare Road (惠福道, wai6 fuk1 dou6) managed to achieve the near-impossible by matching their English and Chinese names both phonetically and semantically.

In Aldrich Street’s translation story, English and Cantonese are creatively intertwined. Situated in Aldrich Bay, the area is named after Colonel Edward Aldrich, who was responsible for formulating the British defence plan and was known for his remarkable effectiveness in rectifying military discipline. When the bay was named after him in 1845, “Aldrich” was converted to 「愛秩序」(ngoi3 dit6 zeoi6) in Chinese, which means “loving discipline” and its Cantonese transliteration.

Eclectic linguistic journey

Linguistic relationships between Hong Kong’s bilingual street names are weird and wonderful. There are times when mistranslations or ill-sounding transliterations lead to hilarious sightings, and there are streets with bilingual names that are completely unrelated. Their Chinese names, however, often tell a different story. Some managed to preserve their indigenous names, while others were shaped by the socio-cultural context of their colonial nomenclature.

Explore the map below by hovering on different streets to see how their bilingual street names are related.

Support HKFP | Code of Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report